Cheong Ek / S21

A word of warning : some of the text and pictures below are quite distressing, it might be wise for some of my younger relatives to skip this bit.

From the ancient splendor around Siem Reap we headed down to Phnom Penh. A much more bleak and distressing period of human history revealed itself as we took a visit to two significant sites of the attrocities committed during the period that the Khmer Rouge held power. Between 1974 and 1979, the Cambodian population of seven million was decimated (around half died, mostly through starvation - 1kg of rice was used to feed 400 people - but also in the detention camps and killing fields scattered through the country).

The Communist Party Of Kampuchea (later named the Khmer Rouge) launched a series of insurgencies across Cambodia from 1968 onwards (against the backdrop of the Vietnam war in neighbouring areas and helped by sympathetic North Vietnamese forces, so reducing the ability of the Cambodian army to oppose it). During the 1970 Cambodian Coup Prince Norodom Sihanouk was deposed by General Lon Nol, who assumed emergency powers and founded the Khmer Republic. In the intervening years, the Khmer Rouge organized themselves winning support from people throughout the country, who thought they were for the restoration of Sihanouk (then in exile in Beijing). Backed by Chinese and North Vietnamese power, they made significant gains in territory and support. By 1973, American assistance ended and by 1975 the Lon Nol government was sufficiently weakened for the Khmer Rouge to seize power. On 17th April 1975, under the guidance of Saloth Sar (or 'Pol Pot' - Political Potential) they did exactly this, marching into Phnom Penh. Initially welcomed, within hours people were being ordered to leave their homes, being told that it would take a few days to find 'enemy combatants'. In reality what happened is that a systematic process of relocation was started, to enable restructuring towards a wholly agricultural based communist society. Classification of people was undertaken, dividing those as either suitable for agricultural work, or an 'intellectual' (including students, engineers, doctors, anyone wearing glasses or having 'smooth hands'). The latter were asked to identify themselves so they could be sent back to the cities - in reality all were shipped off for interrogation in places such as Tuol Sleng (commonly known as S21, a prison converted from the Tuol Svay Prey high school in May 1976 and one of 167 prisons).

Roughly translated Tuol Sleng means a poisonous hill, with additional overtones of bearing guilt - a quite sinister combination of words, and something that would give a terrible foreboding to the place before the context is even known. The classrooms of the former school were converted to prison cells, measuring 0.8m x 2m for single prisoners on the ground floor and 8m x 6m on the upper floors for mass detention. The number of staff at S-21 numbered aroun 1,700 of which 54 worked as "Interrogation Units" - some shockingly young, between the ages of 10 and 15. Detainees were subjected to awful and degrading daily routines and punishments, kept fixed in positions in lines by ankle shackles, stripped of clothes and dignity and having to ask permision to urinate or defecate into small iron buckets (receiving a beating if they failed to ask). Bathing happened as infrequently as twice a month, consisting of the prisoners being rounded up and squirted through a window for a short time with water. Needless to say disease and skin rashes were rife, with no chance of medicines for any sort of treatment. Mealtimes were at 8am and 8pm and consisted of a bowl of rice, prisoners were deliberately kept weak to prevent any sort of defiance or suicide attempts (this was clearly a concern for those who ran the place as there were reams of barbed wire around the windows, and prisoners were constantly observed). Their physical deterioration was further compounded by the routine and sickening application of various tortures, not limited to systematic rape, beatings and the use of insects applied directly to the body.

A typical room, still pretty much how it was found on the ground floor. Box used as a toilet, with bar and fastening used to hold prisoner's limbs during interrogation.

A typical room, still pretty much how it was found on the ground floor. Box used as a toilet, with bar and fastening used to hold prisoner's limbs during interrogation.

View from a window at Tuol Sleng.

View from a window at Tuol Sleng.

20,000 people came through Tuol Sleng, the prison holding around 1,200 - 1,500 at any one time. Imprisonment generally lasted from 2 - 4 months, though significant political prisoners had their misery and terror extended up to seven months. Nearly all ended up in killing fields such as Cheong Ek after interrogation. On their arrival at Tuol Sleng they were photographed, interrogated about the details of their lives so far, stripped of clothes and any possessions before being manacled and placed in cells. The photographs of the prisoners stand side by side with their interrogators (most aged 14-18) in the museum part of the site - the feelings of abject terror shown so clearly their faces as they await the horror of their unknown, immediate future are palpable. Only seven people managed to survive, one of them an artist who's paintings elsewhere in the museum show all too graphically the abhorrent treatment inflicted on himself and others.

20,000 people came through Tuol Sleng, the prison holding around 1,200 - 1,500 at any one time. Imprisonment generally lasted from 2 - 4 months, though significant political prisoners had their misery and terror extended up to seven months. Nearly all ended up in killing fields such as Cheong Ek after interrogation. On their arrival at Tuol Sleng they were photographed, interrogated about the details of their lives so far, stripped of clothes and any possessions before being manacled and placed in cells. The photographs of the prisoners stand side by side with their interrogators (most aged 14-18) in the museum part of the site - the feelings of abject terror shown so clearly their faces as they await the horror of their unknown, immediate future are palpable. Only seven people managed to survive, one of them an artist who's paintings elsewhere in the museum show all too graphically the abhorrent treatment inflicted on himself and others.

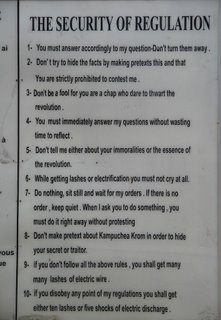

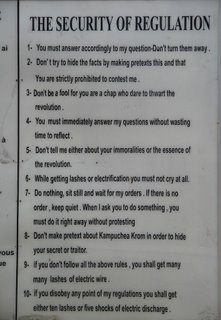

Regulations at Tuol Sleng that prisoners had to abide by.

Regulations at Tuol Sleng that prisoners had to abide by.

Walking around a place such as this, which has only been changed slightly in it's conversion to a museum, is a deeply unsettling experience - inevitable comparisons are raised with respect to the concentration camps of Nazi Germany, and the accounts of the guards questioned since trot out the same 'excuses' of following orders, not having a choice with a few expressing no guilt whatsoever, being thoroughly dehumanised by their training. However, our guides over the course of the day were quick to point out that the Khmer Rouge concentrated wholly inward on the genocide of their own countrymen, there were very few outsiders to suffer the same fate. Recounting the history of the place was clearly very emotionally hard for our guide, who was one of only 10,000 to escape to Vietnam during these four years. She was seven at the time and lost her father, sister and brother to the Khmer Rouge. How she manages to take people around the museum every day, recounting the attrocities against and murders of people who died, possibly in the same circumstances as her own family, is incomprehensible - she confided that she still cries every day about the past. On the walls of the museum, photos of key members of the Khmer Rouge have been violently vandalised - the photo of Pol Pot has been ripped clean off the wall.

When prisoners had outlived the necessity for questioning, they were inevitably led off to the killing fields, of which Cheong Ek is one of the largest. In the photo on the left, each dip in the ground is an excavated mass grave. Around 20,000 people arrived here, none ever escaped (which makes piecing together the history all the more difficult - there are still many uncertainties over what actually happened during this time). One thing is clear, however - that this was the site of one of the worst examples of inhumanity in recent history (and still something which many people at home still do not know the details of - I only had a very rough idea of what went on before coming here). 9,000 human skulls were discovered by farmers in 1980, alerted by an appalling stench whilst working the land, in mass graves just outside of Phnom Penh. 86 mass graves were found in all, yet more bodies remain unexhumed with 11,000 under a lake. This was one of 340 'Killing Fields', scenes of 'production line' murder where people were lined up, their skulls smashed with bamboo (the use of bullets being too expensive to waste, and bamboo is light and easy to wield - so the beatings could continue without the inconvenience of getting tired). They were then kicked into waiting pits - some may have still been just alive when buried.

When prisoners had outlived the necessity for questioning, they were inevitably led off to the killing fields, of which Cheong Ek is one of the largest. In the photo on the left, each dip in the ground is an excavated mass grave. Around 20,000 people arrived here, none ever escaped (which makes piecing together the history all the more difficult - there are still many uncertainties over what actually happened during this time). One thing is clear, however - that this was the site of one of the worst examples of inhumanity in recent history (and still something which many people at home still do not know the details of - I only had a very rough idea of what went on before coming here). 9,000 human skulls were discovered by farmers in 1980, alerted by an appalling stench whilst working the land, in mass graves just outside of Phnom Penh. 86 mass graves were found in all, yet more bodies remain unexhumed with 11,000 under a lake. This was one of 340 'Killing Fields', scenes of 'production line' murder where people were lined up, their skulls smashed with bamboo (the use of bullets being too expensive to waste, and bamboo is light and easy to wield - so the beatings could continue without the inconvenience of getting tired). They were then kicked into waiting pits - some may have still been just alive when buried.

Part of the Buddhist Stupa memorial - the chilling sight of thousands of human skulls, piled floor to ceiling and classified by approximate age and gender.

Part of the Buddhist Stupa memorial - the chilling sight of thousands of human skulls, piled floor to ceiling and classified by approximate age and gender.

Our guide, Sosul was about our age, and gave us some vital insights into the effects felt by people immediately after the Khmer Rouge were deposed and the attrocities discovered. Most people in Cambodia lost at least one family member during this time, and he himself lost his uncle. He said that education has been decimated because of the repression of any form of free thought or learning during the four years - there is still a desperate need for native doctors, teachers, scientists, which is making progress in the city bit in rural areas (most of the country), the emphasis is on farming, driving etc. The need for good schools in the country in turn proliferates ignorance in terms of learning from the past and nurturing the desire to think about progress - incredibly the teaching of history for some children was stopped altogether. He said it also breeds a culture in which parents exploit their own children for short term monetary gain (begging from tourists otherwise they are given no food).

The Cheong Ek memorial, like S-21 where blood still stains the floor, is a very 'raw' reminder of the past. By this I mean that amongst the birdsong and butterflies of the neighbouring fields, pieces of bone and clothing poke up through the ground as you walk about - it took a few seconds to register that we were literally walking through human remains in our sandals. I don't know how long it would have taken us to notice this had Sosul not pointed it out, but they were everywhere - some lying in piles near the trees. Everywhere you look there are huge dips in the floor where the graves had been excavated - some bringing their own macabre evidence as to the circumstances of the dead e.g. headless corpses denoting traitors or nakedness indicating women who had been raped first. Babies were thrown against trees, music was played from speakers to drown out the screams of the victims and the cracking of bones.

The Cheong Ek memorial, like S-21 where blood still stains the floor, is a very 'raw' reminder of the past. By this I mean that amongst the birdsong and butterflies of the neighbouring fields, pieces of bone and clothing poke up through the ground as you walk about - it took a few seconds to register that we were literally walking through human remains in our sandals. I don't know how long it would have taken us to notice this had Sosul not pointed it out, but they were everywhere - some lying in piles near the trees. Everywhere you look there are huge dips in the floor where the graves had been excavated - some bringing their own macabre evidence as to the circumstances of the dead e.g. headless corpses denoting traitors or nakedness indicating women who had been raped first. Babies were thrown against trees, music was played from speakers to drown out the screams of the victims and the cracking of bones.

The sharp leaves of these trees were used to cut throats, using the produce of the land against those who tended it.

The sharp leaves of these trees were used to cut throats, using the produce of the land against those who tended it.

On January 7th 1979, Vietnamese forces entered Phnom Penh and deposed Pol Pot, causing mass defections of Khmer Rouge officers to form the new government. Pol Pot was driven into the countryside, but conflict between the old Khmer Rouge and the new government continued until Pol Pot's trial and imprisonment in 1997. He died in 1998, trials for the remaining perpetrators have been maddeningly slow in coming (though there has been progress recently with international backing), and there are apparantly still elements of the Khmer Rouge in government today. You have only to drive through the countryside to see the effects of the restructuring that took place, Cambodia is still very much an agrarian based area, and there is little development of infrastructure outside the two main cities.

The streets outside Cheoung Ek.

The streets outside Cheoung Ek.

From the ancient splendor around Siem Reap we headed down to Phnom Penh. A much more bleak and distressing period of human history revealed itself as we took a visit to two significant sites of the attrocities committed during the period that the Khmer Rouge held power. Between 1974 and 1979, the Cambodian population of seven million was decimated (around half died, mostly through starvation - 1kg of rice was used to feed 400 people - but also in the detention camps and killing fields scattered through the country).

The Communist Party Of Kampuchea (later named the Khmer Rouge) launched a series of insurgencies across Cambodia from 1968 onwards (against the backdrop of the Vietnam war in neighbouring areas and helped by sympathetic North Vietnamese forces, so reducing the ability of the Cambodian army to oppose it). During the 1970 Cambodian Coup Prince Norodom Sihanouk was deposed by General Lon Nol, who assumed emergency powers and founded the Khmer Republic. In the intervening years, the Khmer Rouge organized themselves winning support from people throughout the country, who thought they were for the restoration of Sihanouk (then in exile in Beijing). Backed by Chinese and North Vietnamese power, they made significant gains in territory and support. By 1973, American assistance ended and by 1975 the Lon Nol government was sufficiently weakened for the Khmer Rouge to seize power. On 17th April 1975, under the guidance of Saloth Sar (or 'Pol Pot' - Political Potential) they did exactly this, marching into Phnom Penh. Initially welcomed, within hours people were being ordered to leave their homes, being told that it would take a few days to find 'enemy combatants'. In reality what happened is that a systematic process of relocation was started, to enable restructuring towards a wholly agricultural based communist society. Classification of people was undertaken, dividing those as either suitable for agricultural work, or an 'intellectual' (including students, engineers, doctors, anyone wearing glasses or having 'smooth hands'). The latter were asked to identify themselves so they could be sent back to the cities - in reality all were shipped off for interrogation in places such as Tuol Sleng (commonly known as S21, a prison converted from the Tuol Svay Prey high school in May 1976 and one of 167 prisons).

Roughly translated Tuol Sleng means a poisonous hill, with additional overtones of bearing guilt - a quite sinister combination of words, and something that would give a terrible foreboding to the place before the context is even known. The classrooms of the former school were converted to prison cells, measuring 0.8m x 2m for single prisoners on the ground floor and 8m x 6m on the upper floors for mass detention. The number of staff at S-21 numbered aroun 1,700 of which 54 worked as "Interrogation Units" - some shockingly young, between the ages of 10 and 15. Detainees were subjected to awful and degrading daily routines and punishments, kept fixed in positions in lines by ankle shackles, stripped of clothes and dignity and having to ask permision to urinate or defecate into small iron buckets (receiving a beating if they failed to ask). Bathing happened as infrequently as twice a month, consisting of the prisoners being rounded up and squirted through a window for a short time with water. Needless to say disease and skin rashes were rife, with no chance of medicines for any sort of treatment. Mealtimes were at 8am and 8pm and consisted of a bowl of rice, prisoners were deliberately kept weak to prevent any sort of defiance or suicide attempts (this was clearly a concern for those who ran the place as there were reams of barbed wire around the windows, and prisoners were constantly observed). Their physical deterioration was further compounded by the routine and sickening application of various tortures, not limited to systematic rape, beatings and the use of insects applied directly to the body.

A typical room, still pretty much how it was found on the ground floor. Box used as a toilet, with bar and fastening used to hold prisoner's limbs during interrogation.

A typical room, still pretty much how it was found on the ground floor. Box used as a toilet, with bar and fastening used to hold prisoner's limbs during interrogation. View from a window at Tuol Sleng.

View from a window at Tuol Sleng. 20,000 people came through Tuol Sleng, the prison holding around 1,200 - 1,500 at any one time. Imprisonment generally lasted from 2 - 4 months, though significant political prisoners had their misery and terror extended up to seven months. Nearly all ended up in killing fields such as Cheong Ek after interrogation. On their arrival at Tuol Sleng they were photographed, interrogated about the details of their lives so far, stripped of clothes and any possessions before being manacled and placed in cells. The photographs of the prisoners stand side by side with their interrogators (most aged 14-18) in the museum part of the site - the feelings of abject terror shown so clearly their faces as they await the horror of their unknown, immediate future are palpable. Only seven people managed to survive, one of them an artist who's paintings elsewhere in the museum show all too graphically the abhorrent treatment inflicted on himself and others.

20,000 people came through Tuol Sleng, the prison holding around 1,200 - 1,500 at any one time. Imprisonment generally lasted from 2 - 4 months, though significant political prisoners had their misery and terror extended up to seven months. Nearly all ended up in killing fields such as Cheong Ek after interrogation. On their arrival at Tuol Sleng they were photographed, interrogated about the details of their lives so far, stripped of clothes and any possessions before being manacled and placed in cells. The photographs of the prisoners stand side by side with their interrogators (most aged 14-18) in the museum part of the site - the feelings of abject terror shown so clearly their faces as they await the horror of their unknown, immediate future are palpable. Only seven people managed to survive, one of them an artist who's paintings elsewhere in the museum show all too graphically the abhorrent treatment inflicted on himself and others. Regulations at Tuol Sleng that prisoners had to abide by.

Regulations at Tuol Sleng that prisoners had to abide by.Walking around a place such as this, which has only been changed slightly in it's conversion to a museum, is a deeply unsettling experience - inevitable comparisons are raised with respect to the concentration camps of Nazi Germany, and the accounts of the guards questioned since trot out the same 'excuses' of following orders, not having a choice with a few expressing no guilt whatsoever, being thoroughly dehumanised by their training. However, our guides over the course of the day were quick to point out that the Khmer Rouge concentrated wholly inward on the genocide of their own countrymen, there were very few outsiders to suffer the same fate. Recounting the history of the place was clearly very emotionally hard for our guide, who was one of only 10,000 to escape to Vietnam during these four years. She was seven at the time and lost her father, sister and brother to the Khmer Rouge. How she manages to take people around the museum every day, recounting the attrocities against and murders of people who died, possibly in the same circumstances as her own family, is incomprehensible - she confided that she still cries every day about the past. On the walls of the museum, photos of key members of the Khmer Rouge have been violently vandalised - the photo of Pol Pot has been ripped clean off the wall.

When prisoners had outlived the necessity for questioning, they were inevitably led off to the killing fields, of which Cheong Ek is one of the largest. In the photo on the left, each dip in the ground is an excavated mass grave. Around 20,000 people arrived here, none ever escaped (which makes piecing together the history all the more difficult - there are still many uncertainties over what actually happened during this time). One thing is clear, however - that this was the site of one of the worst examples of inhumanity in recent history (and still something which many people at home still do not know the details of - I only had a very rough idea of what went on before coming here). 9,000 human skulls were discovered by farmers in 1980, alerted by an appalling stench whilst working the land, in mass graves just outside of Phnom Penh. 86 mass graves were found in all, yet more bodies remain unexhumed with 11,000 under a lake. This was one of 340 'Killing Fields', scenes of 'production line' murder where people were lined up, their skulls smashed with bamboo (the use of bullets being too expensive to waste, and bamboo is light and easy to wield - so the beatings could continue without the inconvenience of getting tired). They were then kicked into waiting pits - some may have still been just alive when buried.

When prisoners had outlived the necessity for questioning, they were inevitably led off to the killing fields, of which Cheong Ek is one of the largest. In the photo on the left, each dip in the ground is an excavated mass grave. Around 20,000 people arrived here, none ever escaped (which makes piecing together the history all the more difficult - there are still many uncertainties over what actually happened during this time). One thing is clear, however - that this was the site of one of the worst examples of inhumanity in recent history (and still something which many people at home still do not know the details of - I only had a very rough idea of what went on before coming here). 9,000 human skulls were discovered by farmers in 1980, alerted by an appalling stench whilst working the land, in mass graves just outside of Phnom Penh. 86 mass graves were found in all, yet more bodies remain unexhumed with 11,000 under a lake. This was one of 340 'Killing Fields', scenes of 'production line' murder where people were lined up, their skulls smashed with bamboo (the use of bullets being too expensive to waste, and bamboo is light and easy to wield - so the beatings could continue without the inconvenience of getting tired). They were then kicked into waiting pits - some may have still been just alive when buried. Part of the Buddhist Stupa memorial - the chilling sight of thousands of human skulls, piled floor to ceiling and classified by approximate age and gender.

Part of the Buddhist Stupa memorial - the chilling sight of thousands of human skulls, piled floor to ceiling and classified by approximate age and gender.Our guide, Sosul was about our age, and gave us some vital insights into the effects felt by people immediately after the Khmer Rouge were deposed and the attrocities discovered. Most people in Cambodia lost at least one family member during this time, and he himself lost his uncle. He said that education has been decimated because of the repression of any form of free thought or learning during the four years - there is still a desperate need for native doctors, teachers, scientists, which is making progress in the city bit in rural areas (most of the country), the emphasis is on farming, driving etc. The need for good schools in the country in turn proliferates ignorance in terms of learning from the past and nurturing the desire to think about progress - incredibly the teaching of history for some children was stopped altogether. He said it also breeds a culture in which parents exploit their own children for short term monetary gain (begging from tourists otherwise they are given no food).

The Cheong Ek memorial, like S-21 where blood still stains the floor, is a very 'raw' reminder of the past. By this I mean that amongst the birdsong and butterflies of the neighbouring fields, pieces of bone and clothing poke up through the ground as you walk about - it took a few seconds to register that we were literally walking through human remains in our sandals. I don't know how long it would have taken us to notice this had Sosul not pointed it out, but they were everywhere - some lying in piles near the trees. Everywhere you look there are huge dips in the floor where the graves had been excavated - some bringing their own macabre evidence as to the circumstances of the dead e.g. headless corpses denoting traitors or nakedness indicating women who had been raped first. Babies were thrown against trees, music was played from speakers to drown out the screams of the victims and the cracking of bones.

The Cheong Ek memorial, like S-21 where blood still stains the floor, is a very 'raw' reminder of the past. By this I mean that amongst the birdsong and butterflies of the neighbouring fields, pieces of bone and clothing poke up through the ground as you walk about - it took a few seconds to register that we were literally walking through human remains in our sandals. I don't know how long it would have taken us to notice this had Sosul not pointed it out, but they were everywhere - some lying in piles near the trees. Everywhere you look there are huge dips in the floor where the graves had been excavated - some bringing their own macabre evidence as to the circumstances of the dead e.g. headless corpses denoting traitors or nakedness indicating women who had been raped first. Babies were thrown against trees, music was played from speakers to drown out the screams of the victims and the cracking of bones. The sharp leaves of these trees were used to cut throats, using the produce of the land against those who tended it.

The sharp leaves of these trees were used to cut throats, using the produce of the land against those who tended it.On January 7th 1979, Vietnamese forces entered Phnom Penh and deposed Pol Pot, causing mass defections of Khmer Rouge officers to form the new government. Pol Pot was driven into the countryside, but conflict between the old Khmer Rouge and the new government continued until Pol Pot's trial and imprisonment in 1997. He died in 1998, trials for the remaining perpetrators have been maddeningly slow in coming (though there has been progress recently with international backing), and there are apparantly still elements of the Khmer Rouge in government today. You have only to drive through the countryside to see the effects of the restructuring that took place, Cambodia is still very much an agrarian based area, and there is little development of infrastructure outside the two main cities.

The streets outside Cheoung Ek.

The streets outside Cheoung Ek.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home