The Vietnam War

The Cold War is a period of history that absoloutely fascinates and appals me. The complete madness and paranoia of two nuclear armed superpowers eyeballing each other, drumming impatient fingers next to "The Button" over the space of Forty years. The course of U.S. foreign policy, shaped extensively by the perceived threat of the spread of Communism steered a good deal of the more jaw-dropping military and political events of the 20th century - such as The Bay Of Pigs, The Cuban Missile Crisis and The Vietnam War. Aside from military activities there were some other pretty mindblowing stories running paralell to it all - e.g. Project Orion, the launch of Sputnik thus kick starting the space race, and the Kennedy assassination. Of course, we have the benefit of hindsight and a handful of decades since, but the opening of files on both sides proves just how close at times we came to near complete destruction of the civilized world (web searching using various combinations of 'cold war' 'accidental' and 'missile launches' is a brilliant way of preventing excess sleep). 'Conventional' warfare was in no short supply either, with The Vietnam War sitting right in the middle of it all - a war which has been described variously as senseless, horrific and immoral. There is of course more to Vietnam than the war, though this is possibly the most immediate thing that most people think of when Vietnam is mentioned. I was keen to find out more about the background to it all, and to see first hand some of the conditions and environments that those involved had to cope with.

Much has been written about the Vietnam War, and I think trying to give a massively detailed account of it here is both outside the scope of this blog, and probably unfeasible given some of the uncertainty and subjectivity of certain events (e.g. The Gulf Of Tonkin Incident). I had only a rudimentary understanding of what lead to half a million combat troops being deployed in a country thousands of miles away from the U.S. that, to all intents, provided no direct threat. Dimly aware of the belief at the time in the "Domino Effect" i.e. if one country in S.E. Asia converted to a Communist system (e.g. Laos, Vietnam), others in the region were likely to follow and so the perceived threat would multiply. In an attempt to find out, I got hold of a copy of In Retrospect, by Bob McNamara (Secretary of Defence for the Kennedy and Johnson administrations) - perhaps not the most unbiased of viewpoints (the war sometimes being referred to as 'McNamara's War') - but it doesn't shy from self-criticism of the complete misunderstanding of the exact situation they were heading into. A continuing theme is one of seeing the changes in S.E. Asia as part of a global Communist movement, rather than a series of separate, national occurences that were closer to what was actually happening. One aspect that surprised me is that there were allegedly no expert advisors on S.E. Asia in the employ of the Pentagon - ironically some of the most useful people in this field had been purged during the McCarthy inquiries. And that the Kennedy administration had some serious doubts at the time about Diem's policies and abilities.

For those of us who were not around to witness accounts of the war at the time, opinions are inevitably shaped by interpretations in popular culture and media - leading sometimes to some wildly wrong assumptions about who was 'right' or 'wrong' - a pretty bogus concept in a lot of places. Apocalypse Now is one of a number of films made since that pull no punches, graphically portray the madness and horror of it all. It also probably wins some sort of prize for the quickest use of an expletive in the history of cinema, with it's opening line of "Saigon ... Shit". While most don't glorify the war, there can sometimes be a distinct lack of sympathy for the perspective of the Vietnamese people (indeed in some depictions, not limited to a couple of pretty dumb computer games, the VC are portrayed as basically savages).

Vietnam is also a very well photo-documented conflict, and I think most people would recognize the look of terror on Kim Phuc's face after an ARVN napalm strike, or the image of Thich Quang Duc committing self-immolation in protest at Ngo Dinh Diem's oppression of Buddhism. The photographs on display at the War Remnants museum especially stuck in my mind - each monochrome still shows a single moment in time, where the expressions of fear and panic on the people involved are frozen, starkly relating their reality and leaving the viewer anxious as to what happened immediately afterwards. It occurred to me that this is probably one of the most dangerous jobs possible - effectively the same situation as the GIs, but without the benefit of a firearm for defence. Indeed there were a number of photographs that were captioned as taken a week or so before the journalist died, or even as the last photo they had taken. This was in a time before the conveniences of automatic cameras with aperture or shutter priorities, the photographers involved would have had to know their craft intimately - no time to mess around and experiment, and certainly no opportunity for re-shooting. It was also in a time long before the advent of digital photography - 'The Camera Never Lies' still having a certain ring of truth to it. Unlike today, where any sixteen year old stoner can get a bent copy of Photoshop off the internet, search for random images on Google and construct any situation imaginable with results that are indistinguishable from reality (in my day we had 30 day trials of Paint Shop Pro and were happy for it). Notable images from the museum include one of an American soldier, roughly stubbled and wide eyed from sleep deprivation desperately clinging to a hand rolled cigarette and looking close to collapse. Or the depiction of an officer facing the camera, the line between anger and fear completely blurred while pointing and shouting - a warning, order or threat ? Another is the shot of a USAF plane being shot down - captured perfectly, yet it was near impossible to tell which direction it's momentum would take it.

The other thing which affected me was the accounts and footage of victims of Agent Orange - one of a number of dioxins and defoliants deployed by the USAF. I knew previously that it had been deployed extensively during the war, and had an idea that it had an effect on the people in the region, but no idea of the extent of it. A short film showed the limb and facial disfigurements suffered by those born in areas exposed to the dioxins - and the unimaginable physical and emotional pain that results. I was particularly disturbed by the display of two foetuses, preserved in formaldehyde bell jars, whose heads were brutally disfigured by the defoliant. You run out of adjectives in trying to describe things like this, suffice to say there is no excuse in my mind for deploying chemicals like this (I understand the tactical importance of mass vegetation clearance, I also understand that effects at the time may not have been fully understood - though it is still a herbicide, deployed over large populated areas and as such inexcusable).

A key part to Viet Cong activity in the South was the Cu Chi Tunnels, an elaborate and far reaching network of tunnels, trap doors and bunkers. These were constructed at first in an ad hoc fashion, to provide the means of moving around and communicating unseen - they eventually expanded to the point where they covered much of the area around Saigon and were a key part of the Tet Offensive. There were many other similar tunnel systems throughout the country, but the ones at Cu Chi were the ones we chose to visit. In this district alone there were around 250km of underground tunnels, including living areas, munitions storage, underground hospitals and kitchens. Air vents were installed so to exit several metres away from where they originated.

A key part to Viet Cong activity in the South was the Cu Chi Tunnels, an elaborate and far reaching network of tunnels, trap doors and bunkers. These were constructed at first in an ad hoc fashion, to provide the means of moving around and communicating unseen - they eventually expanded to the point where they covered much of the area around Saigon and were a key part of the Tet Offensive. There were many other similar tunnel systems throughout the country, but the ones at Cu Chi were the ones we chose to visit. In this district alone there were around 250km of underground tunnels, including living areas, munitions storage, underground hospitals and kitchens. Air vents were installed so to exit several metres away from where they originated.

Innumerable surprise attacks were lauched, often right under the noses of South Vietnamese / U.S. forces - concealed trapdoors making the entrances and exits completely invisible, and laden with booby traps for the unwitting. The sheer level of invention is mind boggling, and fighting this kind of guerrilla war gave U.S. forces a major headache. Indeed, the only 'effective' response seemed to be large scale aerial bombardment - turning the area into one of the most bombed, shelled and defoliated area of the war, if not ever. The area around Cu Chi became known as the Iron Triangle, thousands of troops were sent in to try to flush out VC combatants, but none had any degree of success. Those sent in to the tunnels to try to engage directly were known as Tunnel Rats, and were involved in underground hand to hand and firefights - often with terrible casualty rates. Tactics changed to include sending dogs into the tunnels, but the VC adapted but washing with American soap, so the dogs identified them as friendly - U.S. uniforms left out confused things further. Handlers eventually refused any more activity of this kind as so many were maimed or lost to the tunnels by booby traps. Carpet bombing seemed the only option, but by this time it was a next to worthless gesture given that the tunnels had served their purpose. The VC had no easier time in the tunnels either, despite their apparant tenacity. Of 16,000 cadres serving in the tunnels only 6,000 survived.

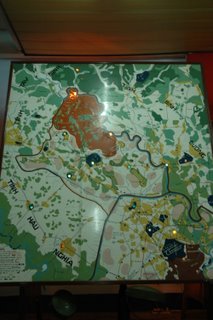

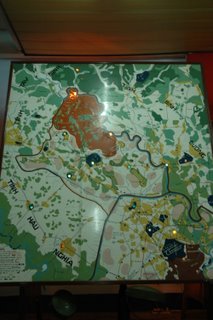

A map of the tunnel network.

A map of the tunnel network.

Inhumane and brutal tactics were not exclusive to either side - this is one of the many horrific inventions deployed by the VC to trap intruders. The victim stands on the suspended platform, which pulls on cables, forcing some vicious looking spikes into the leg.

Inhumane and brutal tactics were not exclusive to either side - this is one of the many horrific inventions deployed by the VC to trap intruders. The victim stands on the suspended platform, which pulls on cables, forcing some vicious looking spikes into the leg.

A swing door trap - when this is closed you would have no idea that it's there ...

One of the guides emerging from the ridiculously small hole - again, once the cover is on you would have absoloutely no clue that there was anything there.

One of the guides emerging from the ridiculously small hole - again, once the cover is on you would have absoloutely no clue that there was anything there.

Much has been written about the Vietnam War, and I think trying to give a massively detailed account of it here is both outside the scope of this blog, and probably unfeasible given some of the uncertainty and subjectivity of certain events (e.g. The Gulf Of Tonkin Incident). I had only a rudimentary understanding of what lead to half a million combat troops being deployed in a country thousands of miles away from the U.S. that, to all intents, provided no direct threat. Dimly aware of the belief at the time in the "Domino Effect" i.e. if one country in S.E. Asia converted to a Communist system (e.g. Laos, Vietnam), others in the region were likely to follow and so the perceived threat would multiply. In an attempt to find out, I got hold of a copy of In Retrospect, by Bob McNamara (Secretary of Defence for the Kennedy and Johnson administrations) - perhaps not the most unbiased of viewpoints (the war sometimes being referred to as 'McNamara's War') - but it doesn't shy from self-criticism of the complete misunderstanding of the exact situation they were heading into. A continuing theme is one of seeing the changes in S.E. Asia as part of a global Communist movement, rather than a series of separate, national occurences that were closer to what was actually happening. One aspect that surprised me is that there were allegedly no expert advisors on S.E. Asia in the employ of the Pentagon - ironically some of the most useful people in this field had been purged during the McCarthy inquiries. And that the Kennedy administration had some serious doubts at the time about Diem's policies and abilities.

For those of us who were not around to witness accounts of the war at the time, opinions are inevitably shaped by interpretations in popular culture and media - leading sometimes to some wildly wrong assumptions about who was 'right' or 'wrong' - a pretty bogus concept in a lot of places. Apocalypse Now is one of a number of films made since that pull no punches, graphically portray the madness and horror of it all. It also probably wins some sort of prize for the quickest use of an expletive in the history of cinema, with it's opening line of "Saigon ... Shit". While most don't glorify the war, there can sometimes be a distinct lack of sympathy for the perspective of the Vietnamese people (indeed in some depictions, not limited to a couple of pretty dumb computer games, the VC are portrayed as basically savages).

Vietnam is also a very well photo-documented conflict, and I think most people would recognize the look of terror on Kim Phuc's face after an ARVN napalm strike, or the image of Thich Quang Duc committing self-immolation in protest at Ngo Dinh Diem's oppression of Buddhism. The photographs on display at the War Remnants museum especially stuck in my mind - each monochrome still shows a single moment in time, where the expressions of fear and panic on the people involved are frozen, starkly relating their reality and leaving the viewer anxious as to what happened immediately afterwards. It occurred to me that this is probably one of the most dangerous jobs possible - effectively the same situation as the GIs, but without the benefit of a firearm for defence. Indeed there were a number of photographs that were captioned as taken a week or so before the journalist died, or even as the last photo they had taken. This was in a time before the conveniences of automatic cameras with aperture or shutter priorities, the photographers involved would have had to know their craft intimately - no time to mess around and experiment, and certainly no opportunity for re-shooting. It was also in a time long before the advent of digital photography - 'The Camera Never Lies' still having a certain ring of truth to it. Unlike today, where any sixteen year old stoner can get a bent copy of Photoshop off the internet, search for random images on Google and construct any situation imaginable with results that are indistinguishable from reality (in my day we had 30 day trials of Paint Shop Pro and were happy for it). Notable images from the museum include one of an American soldier, roughly stubbled and wide eyed from sleep deprivation desperately clinging to a hand rolled cigarette and looking close to collapse. Or the depiction of an officer facing the camera, the line between anger and fear completely blurred while pointing and shouting - a warning, order or threat ? Another is the shot of a USAF plane being shot down - captured perfectly, yet it was near impossible to tell which direction it's momentum would take it.

The other thing which affected me was the accounts and footage of victims of Agent Orange - one of a number of dioxins and defoliants deployed by the USAF. I knew previously that it had been deployed extensively during the war, and had an idea that it had an effect on the people in the region, but no idea of the extent of it. A short film showed the limb and facial disfigurements suffered by those born in areas exposed to the dioxins - and the unimaginable physical and emotional pain that results. I was particularly disturbed by the display of two foetuses, preserved in formaldehyde bell jars, whose heads were brutally disfigured by the defoliant. You run out of adjectives in trying to describe things like this, suffice to say there is no excuse in my mind for deploying chemicals like this (I understand the tactical importance of mass vegetation clearance, I also understand that effects at the time may not have been fully understood - though it is still a herbicide, deployed over large populated areas and as such inexcusable).

A key part to Viet Cong activity in the South was the Cu Chi Tunnels, an elaborate and far reaching network of tunnels, trap doors and bunkers. These were constructed at first in an ad hoc fashion, to provide the means of moving around and communicating unseen - they eventually expanded to the point where they covered much of the area around Saigon and were a key part of the Tet Offensive. There were many other similar tunnel systems throughout the country, but the ones at Cu Chi were the ones we chose to visit. In this district alone there were around 250km of underground tunnels, including living areas, munitions storage, underground hospitals and kitchens. Air vents were installed so to exit several metres away from where they originated.

A key part to Viet Cong activity in the South was the Cu Chi Tunnels, an elaborate and far reaching network of tunnels, trap doors and bunkers. These were constructed at first in an ad hoc fashion, to provide the means of moving around and communicating unseen - they eventually expanded to the point where they covered much of the area around Saigon and were a key part of the Tet Offensive. There were many other similar tunnel systems throughout the country, but the ones at Cu Chi were the ones we chose to visit. In this district alone there were around 250km of underground tunnels, including living areas, munitions storage, underground hospitals and kitchens. Air vents were installed so to exit several metres away from where they originated.Innumerable surprise attacks were lauched, often right under the noses of South Vietnamese / U.S. forces - concealed trapdoors making the entrances and exits completely invisible, and laden with booby traps for the unwitting. The sheer level of invention is mind boggling, and fighting this kind of guerrilla war gave U.S. forces a major headache. Indeed, the only 'effective' response seemed to be large scale aerial bombardment - turning the area into one of the most bombed, shelled and defoliated area of the war, if not ever. The area around Cu Chi became known as the Iron Triangle, thousands of troops were sent in to try to flush out VC combatants, but none had any degree of success. Those sent in to the tunnels to try to engage directly were known as Tunnel Rats, and were involved in underground hand to hand and firefights - often with terrible casualty rates. Tactics changed to include sending dogs into the tunnels, but the VC adapted but washing with American soap, so the dogs identified them as friendly - U.S. uniforms left out confused things further. Handlers eventually refused any more activity of this kind as so many were maimed or lost to the tunnels by booby traps. Carpet bombing seemed the only option, but by this time it was a next to worthless gesture given that the tunnels had served their purpose. The VC had no easier time in the tunnels either, despite their apparant tenacity. Of 16,000 cadres serving in the tunnels only 6,000 survived.

A map of the tunnel network.

A map of the tunnel network. Inhumane and brutal tactics were not exclusive to either side - this is one of the many horrific inventions deployed by the VC to trap intruders. The victim stands on the suspended platform, which pulls on cables, forcing some vicious looking spikes into the leg.

Inhumane and brutal tactics were not exclusive to either side - this is one of the many horrific inventions deployed by the VC to trap intruders. The victim stands on the suspended platform, which pulls on cables, forcing some vicious looking spikes into the leg.

A swing door trap - when this is closed you would have no idea that it's there ...

One of the guides emerging from the ridiculously small hole - again, once the cover is on you would have absoloutely no clue that there was anything there.

One of the guides emerging from the ridiculously small hole - again, once the cover is on you would have absoloutely no clue that there was anything there.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home