Andes Is What Happened Next ...

... Illness. It steals up like a rampant baboon in the night, wrapping it's feathery arms around the unsuspecting and ramming a plunger down the toilet of their dreams. Altitude sickness is a particularly fiendish adversary, there being no real logic to those that it affects, or the circumstances (apart from being very high up, obviously). Well, if you're young with a supercharged metabolism (Dan, Me), then it seems you're slightly more at risk. All of the people we'd met coming back from Cusco assured us that they'd had no problems at all in this department. Liars ! True, most people won't suffer from it unless they're over 3,000 metres above sea level, but I'm pleased to announce that Dan and I took to the beds at a wimpish 2,200 in Arequipa. This is a place famed for Mt. Misti, Andean condor spotting and all sorts of cultural curiosities. We didn't see any of that. We saw toilet bowls. Frequently. The usual advice for coping with altitude sickness is to descend to a more sensible level. Ah, but there's a stronger emotion that lurks in the souls of young men, more formidable even than self pity and self preservation combined ... boredom ! Cue an ill-advised dash up to Puno, a digestion hammering 3,800 masl (after climbing to 4,500 on the way). And spent another three days eating bananas, watching CNN and feeling as sick as dogs. Lower intestines like nervous accordions, brains like upturned bicycles ... watching the days peel away like the paint on the damp ravaged ceiling in Don Tito's. This was not the plan.

Almost a week was written off with a sentance of bread, water, moaning and acetazolamide. We'd planned to go and see a bit of Peru's equally rugged neighbour Bolivia, but travel in this part of the world takes time (significantly more than Lonely Planet's anorexic estimates). La Paz, the de facto capital, is exhausting enough to be overwhelming after only a few days. The streets are crammed full of people selling whatever oddments they expect to be able to sell e.g. an old bloke only selling sink plugs or rusty screws. Most disgusting wares were at the 'Witches Market', a delightful selection of dried toad corpses and llama foetuses. Still, if you can't flog your goods you can always make a fort out of them.

Almost a week was written off with a sentance of bread, water, moaning and acetazolamide. We'd planned to go and see a bit of Peru's equally rugged neighbour Bolivia, but travel in this part of the world takes time (significantly more than Lonely Planet's anorexic estimates). La Paz, the de facto capital, is exhausting enough to be overwhelming after only a few days. The streets are crammed full of people selling whatever oddments they expect to be able to sell e.g. an old bloke only selling sink plugs or rusty screws. Most disgusting wares were at the 'Witches Market', a delightful selection of dried toad corpses and llama foetuses. Still, if you can't flog your goods you can always make a fort out of them.

One thing that is immediately apparant is the fondness the populations of Bolivia and Peru have for any sort of parade or public gathering. I was greeted by a massive display of drums, trumpets and machine guns by the local cops as I stepped out of an internet café in Copacapana (just over the Bolivian border). Like I say, this is no unusual thing and there seemed to be something of this sort every few days, especially in Cusco though it is slightly more disconcerting to see the scene on the left, given that Bolivia has suffered around 60 military coups in it's history (more than any other country). The epic bus journey from Puno to Cusco later on was broken up nicely with a brass band practicing between the stone houses on the way across the plains.

One thing that is immediately apparant is the fondness the populations of Bolivia and Peru have for any sort of parade or public gathering. I was greeted by a massive display of drums, trumpets and machine guns by the local cops as I stepped out of an internet café in Copacapana (just over the Bolivian border). Like I say, this is no unusual thing and there seemed to be something of this sort every few days, especially in Cusco though it is slightly more disconcerting to see the scene on the left, given that Bolivia has suffered around 60 military coups in it's history (more than any other country). The epic bus journey from Puno to Cusco later on was broken up nicely with a brass band practicing between the stone houses on the way across the plains.

Like Santiago, there is a definite culture of wearing smart shoes and keeping them well polished. However, in La Paz the guys who offer the service wear camoflage gear and ski masks. I admit I have no idea why this should be ... whether it started off as a way of masking one's shame or as a sign of solidarity as Dan suggests is unclear. This is a big contrast to Santiago, where there are fixed pedestals set up, and the guys sit around smoking, chatting and reading newspapers until another customer turns up.

Like Santiago, there is a definite culture of wearing smart shoes and keeping them well polished. However, in La Paz the guys who offer the service wear camoflage gear and ski masks. I admit I have no idea why this should be ... whether it started off as a way of masking one's shame or as a sign of solidarity as Dan suggests is unclear. This is a big contrast to Santiago, where there are fixed pedestals set up, and the guys sit around smoking, chatting and reading newspapers until another customer turns up.

Lake Titicaca - the world's highest navigable lake, split between Peru and Bolivia, contains the Uros islands. These are a collection of 43 artificial masses constructed of Totora reeds (which typically last around 30 odd years before a new island is constructed), stable enough for semi-permanant housing and keeping livestock. They were originally created by the Uro people, in order to escape domination by the Inca ... there are around 3,000 descendants of the Uro (though most live on the mainland). The lake itself is used by the Bolivian navy for exercises, as the country itself has been landlocked since The War Of The Pacific. This kid tagged along for the ride in the boat that his dad was steering, and proved to be a total riot, pulling on his dad's tracksuit drawstring and insisting on being allowed to 'help' steer the canoe.

Lake Titicaca - the world's highest navigable lake, split between Peru and Bolivia, contains the Uros islands. These are a collection of 43 artificial masses constructed of Totora reeds (which typically last around 30 odd years before a new island is constructed), stable enough for semi-permanant housing and keeping livestock. They were originally created by the Uro people, in order to escape domination by the Inca ... there are around 3,000 descendants of the Uro (though most live on the mainland). The lake itself is used by the Bolivian navy for exercises, as the country itself has been landlocked since The War Of The Pacific. This kid tagged along for the ride in the boat that his dad was steering, and proved to be a total riot, pulling on his dad's tracksuit drawstring and insisting on being allowed to 'help' steer the canoe.

The focal point for anyone's trip to Peru is inevitably the journey to Machu Picchu, often by way of hiking the Inca Trail. First stop was the Sacred Valley (generally defined as the area between Pisac and Ollantaytambo), a fertile agricultural region that was essential for the Incas and continues to supply much of Cusco's produce today. On the left is a shot of the village we visited, bumping up a winding and terrifyingly narrow mud track. The villagers make all manner of goods woven from Alpaca wool, and coloured with natural dyes - I love the sort of slings that the kids are carried around in here ! We stopped over in Ollantaytambo for a brief rest before hitting the trail at km82 the next day for a relatively easy going 12-14km saunter up to the Yunkachimpa campsite.

The focal point for anyone's trip to Peru is inevitably the journey to Machu Picchu, often by way of hiking the Inca Trail. First stop was the Sacred Valley (generally defined as the area between Pisac and Ollantaytambo), a fertile agricultural region that was essential for the Incas and continues to supply much of Cusco's produce today. On the left is a shot of the village we visited, bumping up a winding and terrifyingly narrow mud track. The villagers make all manner of goods woven from Alpaca wool, and coloured with natural dyes - I love the sort of slings that the kids are carried around in here ! We stopped over in Ollantaytambo for a brief rest before hitting the trail at km82 the next day for a relatively easy going 12-14km saunter up to the Yunkachimpa campsite.

Our two guides along the trail were the tireless Percy (pictured left), and relatively new addition Herman. Reading the Inca Trail threads on travel forums will throw up a few horror stories about certain companies that operate around Cusco. Percy seemed to genuinely care about what he was doing though, and during our time with the group would refer to us as "his family". Sixteen people is a large group by my standards, and it all went as smoothly as you could expect. I was a bit puzzled by the fact that for the first few days there were no group meals or even some drinks around a table - surely it's important for people to break the ice and get to know each other sooner rather than later with tours like this. However, I think perhaps this was being kept in reserve for the end of the first days hike ...

Our two guides along the trail were the tireless Percy (pictured left), and relatively new addition Herman. Reading the Inca Trail threads on travel forums will throw up a few horror stories about certain companies that operate around Cusco. Percy seemed to genuinely care about what he was doing though, and during our time with the group would refer to us as "his family". Sixteen people is a large group by my standards, and it all went as smoothly as you could expect. I was a bit puzzled by the fact that for the first few days there were no group meals or even some drinks around a table - surely it's important for people to break the ice and get to know each other sooner rather than later with tours like this. However, I think perhaps this was being kept in reserve for the end of the first days hike ...

... where Percy insisted that we should all introduce ourselves to the porters and each other. Twenty two porters in all, these guys work like you would not believe. They're responsible for carrying the camping gear, setting up the tents, cooking, carrying the duffel bags and just about everything else. It was all done amazingly smoothly, and they shot up the trail like greased springs, leaving us panting in the dust. They come from a variety of villages in the area, with Quechan as the native language. It was explained that there's a bit of prejudice towards Quechan culture in Cusco and other large cities, with a lot of pressure on people speaking Spanish rather than Quechan (or Aramaya). I felt like a bit of a cock sometimes greeting them along the trail with a bouyant "Buenos Dias !", but then again it was the only common means of communication. Well, that and handing out the coca leaves, which were always well received.

... where Percy insisted that we should all introduce ourselves to the porters and each other. Twenty two porters in all, these guys work like you would not believe. They're responsible for carrying the camping gear, setting up the tents, cooking, carrying the duffel bags and just about everything else. It was all done amazingly smoothly, and they shot up the trail like greased springs, leaving us panting in the dust. They come from a variety of villages in the area, with Quechan as the native language. It was explained that there's a bit of prejudice towards Quechan culture in Cusco and other large cities, with a lot of pressure on people speaking Spanish rather than Quechan (or Aramaya). I felt like a bit of a cock sometimes greeting them along the trail with a bouyant "Buenos Dias !", but then again it was the only common means of communication. Well, that and handing out the coca leaves, which were always well received.

The undaunted adventurers, totally knackered at the top of the thousand metre climb to Warmiwañusca ("Dead Woman's Pass") - the highest point of the trek at 4,200 masl. The trial winds it's way up, down and around numerous different peaks, and the weather is extremely changeable with several microclimates operating at different elevations. On the way up to the pass the temperature dropped suddenly as a chill wind blew in from the top, and the air got noticeably thinner. Look at that, happy as children that have just heard their dad swear.

The undaunted adventurers, totally knackered at the top of the thousand metre climb to Warmiwañusca ("Dead Woman's Pass") - the highest point of the trek at 4,200 masl. The trial winds it's way up, down and around numerous different peaks, and the weather is extremely changeable with several microclimates operating at different elevations. On the way up to the pass the temperature dropped suddenly as a chill wind blew in from the top, and the air got noticeably thinner. Look at that, happy as children that have just heard their dad swear.

The downward spiral from Dead Woman's Pass. There are three high altitude passes along the way and the inclines are hard going in places. Altitude sickness thankfully wasn't so much of a problem along the trail for us, and I took advantage of the local custom of chewing Coca leaves to alleviate the symptoms of tingling extremeties and general knackerdness. They initially tasted like dried tea, but soon took on the consistency of wet grass at the bottom of a mower box. Yes, these are the same leaves that are used as the base ingredient for cocaine (scandalous !), but rest assured that's about all you can say in terms of similarity. Chewing coca is a big part of Andean culture, and given the perceived link to the illegal narcotics that flood the cities in the developed world, it's no wonder it's largely misunderstood and demonised by other countries' govenments. I learned a bit about this in the excellent Coca Museum in La Paz - coca had been a part of indiginous Andean cultures for thousands of years before the Conquistadores arrived. It was proclaimed to be 'demonic' despite the relatively mild effects and the fact that it was essential for coping with the excruciating work in the mines. Effects of chewing coca include a reduced appetite, a perceived increase in energy and increased ability to breathe properly in the thin air of the highlands. Note that there is actually the same amount of oxygen in the air up here, it's the pressure that is reduced, meaning that it's far more difficult to get the necessary amount pushed into the lungs (which amounts to the same thing, really). In any case, coca was so necessary to daily life in the hard times of the Spanish conquest that it was eventually worth more than the equivalent weight in either gold or silver (not that there was any shortage of that either, at least not before it was nicked). Over in Bolivia, Evo Morales has promised to legalize the cultivation of coca, asserting it's difference to processed cocaine (which is sure to get up the nose of the U.S.)

The downward spiral from Dead Woman's Pass. There are three high altitude passes along the way and the inclines are hard going in places. Altitude sickness thankfully wasn't so much of a problem along the trail for us, and I took advantage of the local custom of chewing Coca leaves to alleviate the symptoms of tingling extremeties and general knackerdness. They initially tasted like dried tea, but soon took on the consistency of wet grass at the bottom of a mower box. Yes, these are the same leaves that are used as the base ingredient for cocaine (scandalous !), but rest assured that's about all you can say in terms of similarity. Chewing coca is a big part of Andean culture, and given the perceived link to the illegal narcotics that flood the cities in the developed world, it's no wonder it's largely misunderstood and demonised by other countries' govenments. I learned a bit about this in the excellent Coca Museum in La Paz - coca had been a part of indiginous Andean cultures for thousands of years before the Conquistadores arrived. It was proclaimed to be 'demonic' despite the relatively mild effects and the fact that it was essential for coping with the excruciating work in the mines. Effects of chewing coca include a reduced appetite, a perceived increase in energy and increased ability to breathe properly in the thin air of the highlands. Note that there is actually the same amount of oxygen in the air up here, it's the pressure that is reduced, meaning that it's far more difficult to get the necessary amount pushed into the lungs (which amounts to the same thing, really). In any case, coca was so necessary to daily life in the hard times of the Spanish conquest that it was eventually worth more than the equivalent weight in either gold or silver (not that there was any shortage of that either, at least not before it was nicked). Over in Bolivia, Evo Morales has promised to legalize the cultivation of coca, asserting it's difference to processed cocaine (which is sure to get up the nose of the U.S.)

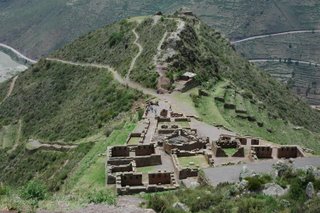

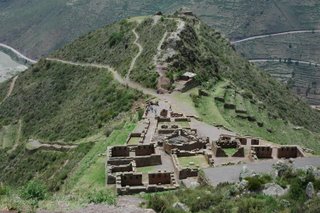

The attraction of the trail is not just the endless walking, sweating and lack of sleep. No, there's also an abundance of archaeological sites to explore. The stonework in these areas varied in appearance and construction techniques, but some it was utterly amazing, especially considering that iron and steel were not used in this area (gold and silver were). Some of it was shaped around stone formations found naturally, adding a great deal of strength, but the brickwork itself was exceptionally precise. Only hairline gaps were visible between blocks, and they were constructed in such a way to be virtually untouched by the earthquakes that rocked the area (unlike the later Spanish churches, which all collapsed). The terraces along the side of this peak are standard features at many of the sites in the area - opinions differ as to what purpose they serve, but it's mostly accepted that they serve as retaining walls - preventing erosion and landslides during the heavy rainfall in the wet season. Also present at the sites were wall holes for burials (mummification was extensively practiced, in the belief that when a person dies they should be returned to the earth and later resurrected). Percy also explained some of the more gruesome practices that took place including animal and human sacrifices - quite a few of the young women in the area were deliberately put to death. Those considered to be the most physically beautiful (provided they had not had their first menstruation) got the short end of the stick, as a sacrifice of this kind was considered to be an aid to the fertility of the land. Allegedly there was some sort of acclaim or prestige in this, as you would be acting as a sort of bridge between the human world and the spirit world, though I think humble anonymity would be much preferable.

The attraction of the trail is not just the endless walking, sweating and lack of sleep. No, there's also an abundance of archaeological sites to explore. The stonework in these areas varied in appearance and construction techniques, but some it was utterly amazing, especially considering that iron and steel were not used in this area (gold and silver were). Some of it was shaped around stone formations found naturally, adding a great deal of strength, but the brickwork itself was exceptionally precise. Only hairline gaps were visible between blocks, and they were constructed in such a way to be virtually untouched by the earthquakes that rocked the area (unlike the later Spanish churches, which all collapsed). The terraces along the side of this peak are standard features at many of the sites in the area - opinions differ as to what purpose they serve, but it's mostly accepted that they serve as retaining walls - preventing erosion and landslides during the heavy rainfall in the wet season. Also present at the sites were wall holes for burials (mummification was extensively practiced, in the belief that when a person dies they should be returned to the earth and later resurrected). Percy also explained some of the more gruesome practices that took place including animal and human sacrifices - quite a few of the young women in the area were deliberately put to death. Those considered to be the most physically beautiful (provided they had not had their first menstruation) got the short end of the stick, as a sacrifice of this kind was considered to be an aid to the fertility of the land. Allegedly there was some sort of acclaim or prestige in this, as you would be acting as a sort of bridge between the human world and the spirit world, though I think humble anonymity would be much preferable.

So, did I suffer from vertigo along the trail ? Amazingly, for the most part I just got on with it, and concentrating on pumping the legs and getting up the slopes, trying to bite whole chunks of oxygen out of the thinning air. I had my concerns before the start as to how developed the trail was going to be - as in I had a horrible vision that big parts of it would be concrete steps, safety rails and all the trappings of a comfortable tourist experience. I'm happy to report that this was not the case at all, and there was pretty much no safety net the whole way. Perhaps a token piece of wooden railing on some rickety bridge somewhere, for about a metre at a time. The drops were sheer in a lot of places, but it wasn't until Machu Picchu itself that I had time to think about what I was doing, and some proper hesitancy set in (I saw one poor girl bawling her head off at the top of the Sundial). Let me explain what this sort of vertigo is like ... it's not that I just feel as if there's a danger of falling over the edge, it's as if I've already gone over. So you can imagine my horror when I heard that one of our group had done exactly that, whilst speeding along a wet cliff edge on the descent to Machu Picchu (this section inspires some seriously childish and outright dangerous behaviour as everyone tries to be first to the Sun Gate and beyond). I'm sure he realises the seriousness of the mistake now, but he had a very lucky escape in being able to grab some vines as soon as he went over. He was also extremely lucky that there were other people who noticed and were able to yank him back up - it could very, very easily have ended in tragedy.

So, did I suffer from vertigo along the trail ? Amazingly, for the most part I just got on with it, and concentrating on pumping the legs and getting up the slopes, trying to bite whole chunks of oxygen out of the thinning air. I had my concerns before the start as to how developed the trail was going to be - as in I had a horrible vision that big parts of it would be concrete steps, safety rails and all the trappings of a comfortable tourist experience. I'm happy to report that this was not the case at all, and there was pretty much no safety net the whole way. Perhaps a token piece of wooden railing on some rickety bridge somewhere, for about a metre at a time. The drops were sheer in a lot of places, but it wasn't until Machu Picchu itself that I had time to think about what I was doing, and some proper hesitancy set in (I saw one poor girl bawling her head off at the top of the Sundial). Let me explain what this sort of vertigo is like ... it's not that I just feel as if there's a danger of falling over the edge, it's as if I've already gone over. So you can imagine my horror when I heard that one of our group had done exactly that, whilst speeding along a wet cliff edge on the descent to Machu Picchu (this section inspires some seriously childish and outright dangerous behaviour as everyone tries to be first to the Sun Gate and beyond). I'm sure he realises the seriousness of the mistake now, but he had a very lucky escape in being able to grab some vines as soon as he went over. He was also extremely lucky that there were other people who noticed and were able to yank him back up - it could very, very easily have ended in tragedy.

The scene that greeted us as the sun went down just before the third night's camping at Chakiqocha. The following day involved a dizzying and joint-worrying descent of around a thousand metres before rolling in to camp at Wiñawayna (meaning "Forever Young" - you will be if you fall over the bloody edge). For the preceeding days leading up to this we had walked longer than most other groups in order to secure campsites further along the trail, with the idea being that on the last night we could camp 10 minutes from the gated entrance to the last descent. This meant getting the relative luxury of a lie in until 4am, but also necessitated camping on the edge of cliffs so steep that getting up for a pee in the middle of the night was a life or death exercise. I'm not sure if it was the sudden increase in oxygen, or the fact that I was lying on a slope leading off into the void, but I felt highly agitated the whole night and had serious trouble sleeping (even by the standards of an arch insomniac like myself). We then had a frenetic run down the cliff tracks in the pitch dark, flashlights flailing, so that we could position ourselves for a lead along the trail proper. Fat lot of good it did me, as I sprained my ankle five minutes after getting onto it. Normally this would just mean getting ice on it immediately and resting up ... however I had to hike six more kilometres and could not get a good look the rapidly forming egg until the evening. Thus I was hobbling around for a good long while afterwards. My weak ankles are a legacy of injuries sustained from nearly ten years of drunken skateboarding, from the multi-stories of Windsor to the gravel plagued slopes of Southbank. Like a lot of other teenage pursuits, my only regret is that I didn't do it more before the consequences caught up with me.

The scene that greeted us as the sun went down just before the third night's camping at Chakiqocha. The following day involved a dizzying and joint-worrying descent of around a thousand metres before rolling in to camp at Wiñawayna (meaning "Forever Young" - you will be if you fall over the bloody edge). For the preceeding days leading up to this we had walked longer than most other groups in order to secure campsites further along the trail, with the idea being that on the last night we could camp 10 minutes from the gated entrance to the last descent. This meant getting the relative luxury of a lie in until 4am, but also necessitated camping on the edge of cliffs so steep that getting up for a pee in the middle of the night was a life or death exercise. I'm not sure if it was the sudden increase in oxygen, or the fact that I was lying on a slope leading off into the void, but I felt highly agitated the whole night and had serious trouble sleeping (even by the standards of an arch insomniac like myself). We then had a frenetic run down the cliff tracks in the pitch dark, flashlights flailing, so that we could position ourselves for a lead along the trail proper. Fat lot of good it did me, as I sprained my ankle five minutes after getting onto it. Normally this would just mean getting ice on it immediately and resting up ... however I had to hike six more kilometres and could not get a good look the rapidly forming egg until the evening. Thus I was hobbling around for a good long while afterwards. My weak ankles are a legacy of injuries sustained from nearly ten years of drunken skateboarding, from the multi-stories of Windsor to the gravel plagued slopes of Southbank. Like a lot of other teenage pursuits, my only regret is that I didn't do it more before the consequences caught up with me.

And at 2,400 masl sits Machu Picchu ("Old Peak"), at last. After all the hassle of hobbling up to the Sun Gate on a stick, I was greeted by the stunning sight of ... a load of fog. Fortunately it didn't last, and I made it down the gut wrenching gradients to join the rest of the group. Probably the best known, and least known about, archaeological site in South America. Lost to the rest of the world until 1911 when it was re-discovered by Hiram Bingham, an American historian at Yale. The site was covered with thick vegetation, and the main clearing and restoration efforts lasted from 1912 to 1915. Bingham was later accused of removing around 5,000 artifacts from the site. Despite efforts by the Peruvian government to get them back, they are still in the possesion of Yale. Left is the sort of scene you'd probably get on tourism adverts ... the soundtrack would probably be a load of dreamy synth pads, reverbed piano arpeggios and perhaps a frenetic Charango. Personally I'd add a sample of a shrieking bird of prey pouncing on a guinea pig and cracking it's skull open with razor sharp beak to feast on the nut flavoured brains inside. Which explains why I can never work in advertising ever again.

And at 2,400 masl sits Machu Picchu ("Old Peak"), at last. After all the hassle of hobbling up to the Sun Gate on a stick, I was greeted by the stunning sight of ... a load of fog. Fortunately it didn't last, and I made it down the gut wrenching gradients to join the rest of the group. Probably the best known, and least known about, archaeological site in South America. Lost to the rest of the world until 1911 when it was re-discovered by Hiram Bingham, an American historian at Yale. The site was covered with thick vegetation, and the main clearing and restoration efforts lasted from 1912 to 1915. Bingham was later accused of removing around 5,000 artifacts from the site. Despite efforts by the Peruvian government to get them back, they are still in the possesion of Yale. Left is the sort of scene you'd probably get on tourism adverts ... the soundtrack would probably be a load of dreamy synth pads, reverbed piano arpeggios and perhaps a frenetic Charango. Personally I'd add a sample of a shrieking bird of prey pouncing on a guinea pig and cracking it's skull open with razor sharp beak to feast on the nut flavoured brains inside. Which explains why I can never work in advertising ever again.

The original construction of the city was thought to have started in about 1440, and was inhabited up to the Spanish conquest of 1532. It's thought that it was primarily a retreat for Incan nobility (who were disposed once the spanish arrived on the scene - the Quechan workers were spared as they obviously were needed for such things as farming and other labour). As mentioned, the quality of stonework in the area is exceptional, and insulation was provided in the form of a mixture of clay, cactus juice and sand. Much of the stone is white granite, which due to a very slow crystalization process naturally forms cracks and fissures - exploitable with a few well placed holes and stakes. Once cracked into shape, they were polished off to a fine grade with white sand. The Inca were no slouches when it came to disciplines like geometry as well, as the sundial accurately points to all corners of the compass (it's not known how this was achieved). Percy seemed to think that the tilt at the top of it matched the tilt of the earth itself, calibrated with respect to other sundials hundreds of miles away. If this is indeed true, it's pretty mind blowing as it was achieved without any form of modern positioning systems and no way of practically verifying it.

This spitting git is a Llama, standard sight on the trail and elsewhere in the highlands of Peru. Like the Alpaca, it's a distant relative of the camel, a fact told to me by a racist man standing next to one in Tasmania. The Alpaca also happens to be a local favourite in restaurants everywhere, and tastes like beef but tougher and saltier. At the end of the hike I also got to sample some Guinea Pig, which tasted not unlike duck. I'm glad I ate one of the bastards, as there were a few of them milling around on the trails, blocking the way and generally making things far more difficult than they needed to be. I can also add them to the list of Gross Things Ingested, not limited to scorpion (tastes like roasted soy), wood grubs (tastes like Wotsits) and cat food (tastes like cat's breath).

This spitting git is a Llama, standard sight on the trail and elsewhere in the highlands of Peru. Like the Alpaca, it's a distant relative of the camel, a fact told to me by a racist man standing next to one in Tasmania. The Alpaca also happens to be a local favourite in restaurants everywhere, and tastes like beef but tougher and saltier. At the end of the hike I also got to sample some Guinea Pig, which tasted not unlike duck. I'm glad I ate one of the bastards, as there were a few of them milling around on the trails, blocking the way and generally making things far more difficult than they needed to be. I can also add them to the list of Gross Things Ingested, not limited to scorpion (tastes like roasted soy), wood grubs (tastes like Wotsits) and cat food (tastes like cat's breath).

THE OCHO !! There's only so much tramping you can do each day, and there was a fair bit of free time in the evenings (more than I would have liked really, as I had left all forms of entertainment back in Cusco). But the bored will adapt ! Favourite distractions included Sapo (literally "Toad") which involved throwing brass chunks at a realistically fashioned amphibian. Also cliff edge rounds of hackysack (yes the inevitable happened), and sixth form favourite "Shithead". Though I grew up with the orthodox rules of Windsor Boys School, I have no idea where the girls picked up the crackheaded idea that wildcards have to be played in sequence. And since when do you play below a six for crying out loud ? Everyone knows it's the eight. What the hell are they teaching kids today anyway ? Completely underprepared for the larger world. I think I displayed remarkable patience under the circumstances, especially as this is what my taxes are paying for. However, one excellent modification was turning it into an excuse for getting pissed, a language that transcends all cultural and educational barriers. When laying the now-neutered eight, the players will simultaneously roar "The Ocho !" as loud as they can, knock bottles and swig deep. I am told this is something to do with the film Dodgeball. I don't really care about that, all I know is that it scandalized all the other squares in the campsite and that I thought it was hilarious. The hand that Drew is about to play has not one, but three eights ... the resulting bellows almost derailed the train.

THE OCHO !! There's only so much tramping you can do each day, and there was a fair bit of free time in the evenings (more than I would have liked really, as I had left all forms of entertainment back in Cusco). But the bored will adapt ! Favourite distractions included Sapo (literally "Toad") which involved throwing brass chunks at a realistically fashioned amphibian. Also cliff edge rounds of hackysack (yes the inevitable happened), and sixth form favourite "Shithead". Though I grew up with the orthodox rules of Windsor Boys School, I have no idea where the girls picked up the crackheaded idea that wildcards have to be played in sequence. And since when do you play below a six for crying out loud ? Everyone knows it's the eight. What the hell are they teaching kids today anyway ? Completely underprepared for the larger world. I think I displayed remarkable patience under the circumstances, especially as this is what my taxes are paying for. However, one excellent modification was turning it into an excuse for getting pissed, a language that transcends all cultural and educational barriers. When laying the now-neutered eight, the players will simultaneously roar "The Ocho !" as loud as they can, knock bottles and swig deep. I am told this is something to do with the film Dodgeball. I don't really care about that, all I know is that it scandalized all the other squares in the campsite and that I thought it was hilarious. The hand that Drew is about to play has not one, but three eights ... the resulting bellows almost derailed the train.

Almost a week was written off with a sentance of bread, water, moaning and acetazolamide. We'd planned to go and see a bit of Peru's equally rugged neighbour Bolivia, but travel in this part of the world takes time (significantly more than Lonely Planet's anorexic estimates). La Paz, the de facto capital, is exhausting enough to be overwhelming after only a few days. The streets are crammed full of people selling whatever oddments they expect to be able to sell e.g. an old bloke only selling sink plugs or rusty screws. Most disgusting wares were at the 'Witches Market', a delightful selection of dried toad corpses and llama foetuses. Still, if you can't flog your goods you can always make a fort out of them.

Almost a week was written off with a sentance of bread, water, moaning and acetazolamide. We'd planned to go and see a bit of Peru's equally rugged neighbour Bolivia, but travel in this part of the world takes time (significantly more than Lonely Planet's anorexic estimates). La Paz, the de facto capital, is exhausting enough to be overwhelming after only a few days. The streets are crammed full of people selling whatever oddments they expect to be able to sell e.g. an old bloke only selling sink plugs or rusty screws. Most disgusting wares were at the 'Witches Market', a delightful selection of dried toad corpses and llama foetuses. Still, if you can't flog your goods you can always make a fort out of them. One thing that is immediately apparant is the fondness the populations of Bolivia and Peru have for any sort of parade or public gathering. I was greeted by a massive display of drums, trumpets and machine guns by the local cops as I stepped out of an internet café in Copacapana (just over the Bolivian border). Like I say, this is no unusual thing and there seemed to be something of this sort every few days, especially in Cusco though it is slightly more disconcerting to see the scene on the left, given that Bolivia has suffered around 60 military coups in it's history (more than any other country). The epic bus journey from Puno to Cusco later on was broken up nicely with a brass band practicing between the stone houses on the way across the plains.

One thing that is immediately apparant is the fondness the populations of Bolivia and Peru have for any sort of parade or public gathering. I was greeted by a massive display of drums, trumpets and machine guns by the local cops as I stepped out of an internet café in Copacapana (just over the Bolivian border). Like I say, this is no unusual thing and there seemed to be something of this sort every few days, especially in Cusco though it is slightly more disconcerting to see the scene on the left, given that Bolivia has suffered around 60 military coups in it's history (more than any other country). The epic bus journey from Puno to Cusco later on was broken up nicely with a brass band practicing between the stone houses on the way across the plains. Like Santiago, there is a definite culture of wearing smart shoes and keeping them well polished. However, in La Paz the guys who offer the service wear camoflage gear and ski masks. I admit I have no idea why this should be ... whether it started off as a way of masking one's shame or as a sign of solidarity as Dan suggests is unclear. This is a big contrast to Santiago, where there are fixed pedestals set up, and the guys sit around smoking, chatting and reading newspapers until another customer turns up.

Like Santiago, there is a definite culture of wearing smart shoes and keeping them well polished. However, in La Paz the guys who offer the service wear camoflage gear and ski masks. I admit I have no idea why this should be ... whether it started off as a way of masking one's shame or as a sign of solidarity as Dan suggests is unclear. This is a big contrast to Santiago, where there are fixed pedestals set up, and the guys sit around smoking, chatting and reading newspapers until another customer turns up. Lake Titicaca - the world's highest navigable lake, split between Peru and Bolivia, contains the Uros islands. These are a collection of 43 artificial masses constructed of Totora reeds (which typically last around 30 odd years before a new island is constructed), stable enough for semi-permanant housing and keeping livestock. They were originally created by the Uro people, in order to escape domination by the Inca ... there are around 3,000 descendants of the Uro (though most live on the mainland). The lake itself is used by the Bolivian navy for exercises, as the country itself has been landlocked since The War Of The Pacific. This kid tagged along for the ride in the boat that his dad was steering, and proved to be a total riot, pulling on his dad's tracksuit drawstring and insisting on being allowed to 'help' steer the canoe.

Lake Titicaca - the world's highest navigable lake, split between Peru and Bolivia, contains the Uros islands. These are a collection of 43 artificial masses constructed of Totora reeds (which typically last around 30 odd years before a new island is constructed), stable enough for semi-permanant housing and keeping livestock. They were originally created by the Uro people, in order to escape domination by the Inca ... there are around 3,000 descendants of the Uro (though most live on the mainland). The lake itself is used by the Bolivian navy for exercises, as the country itself has been landlocked since The War Of The Pacific. This kid tagged along for the ride in the boat that his dad was steering, and proved to be a total riot, pulling on his dad's tracksuit drawstring and insisting on being allowed to 'help' steer the canoe. The focal point for anyone's trip to Peru is inevitably the journey to Machu Picchu, often by way of hiking the Inca Trail. First stop was the Sacred Valley (generally defined as the area between Pisac and Ollantaytambo), a fertile agricultural region that was essential for the Incas and continues to supply much of Cusco's produce today. On the left is a shot of the village we visited, bumping up a winding and terrifyingly narrow mud track. The villagers make all manner of goods woven from Alpaca wool, and coloured with natural dyes - I love the sort of slings that the kids are carried around in here ! We stopped over in Ollantaytambo for a brief rest before hitting the trail at km82 the next day for a relatively easy going 12-14km saunter up to the Yunkachimpa campsite.

The focal point for anyone's trip to Peru is inevitably the journey to Machu Picchu, often by way of hiking the Inca Trail. First stop was the Sacred Valley (generally defined as the area between Pisac and Ollantaytambo), a fertile agricultural region that was essential for the Incas and continues to supply much of Cusco's produce today. On the left is a shot of the village we visited, bumping up a winding and terrifyingly narrow mud track. The villagers make all manner of goods woven from Alpaca wool, and coloured with natural dyes - I love the sort of slings that the kids are carried around in here ! We stopped over in Ollantaytambo for a brief rest before hitting the trail at km82 the next day for a relatively easy going 12-14km saunter up to the Yunkachimpa campsite. Our two guides along the trail were the tireless Percy (pictured left), and relatively new addition Herman. Reading the Inca Trail threads on travel forums will throw up a few horror stories about certain companies that operate around Cusco. Percy seemed to genuinely care about what he was doing though, and during our time with the group would refer to us as "his family". Sixteen people is a large group by my standards, and it all went as smoothly as you could expect. I was a bit puzzled by the fact that for the first few days there were no group meals or even some drinks around a table - surely it's important for people to break the ice and get to know each other sooner rather than later with tours like this. However, I think perhaps this was being kept in reserve for the end of the first days hike ...

Our two guides along the trail were the tireless Percy (pictured left), and relatively new addition Herman. Reading the Inca Trail threads on travel forums will throw up a few horror stories about certain companies that operate around Cusco. Percy seemed to genuinely care about what he was doing though, and during our time with the group would refer to us as "his family". Sixteen people is a large group by my standards, and it all went as smoothly as you could expect. I was a bit puzzled by the fact that for the first few days there were no group meals or even some drinks around a table - surely it's important for people to break the ice and get to know each other sooner rather than later with tours like this. However, I think perhaps this was being kept in reserve for the end of the first days hike ... ... where Percy insisted that we should all introduce ourselves to the porters and each other. Twenty two porters in all, these guys work like you would not believe. They're responsible for carrying the camping gear, setting up the tents, cooking, carrying the duffel bags and just about everything else. It was all done amazingly smoothly, and they shot up the trail like greased springs, leaving us panting in the dust. They come from a variety of villages in the area, with Quechan as the native language. It was explained that there's a bit of prejudice towards Quechan culture in Cusco and other large cities, with a lot of pressure on people speaking Spanish rather than Quechan (or Aramaya). I felt like a bit of a cock sometimes greeting them along the trail with a bouyant "Buenos Dias !", but then again it was the only common means of communication. Well, that and handing out the coca leaves, which were always well received.

... where Percy insisted that we should all introduce ourselves to the porters and each other. Twenty two porters in all, these guys work like you would not believe. They're responsible for carrying the camping gear, setting up the tents, cooking, carrying the duffel bags and just about everything else. It was all done amazingly smoothly, and they shot up the trail like greased springs, leaving us panting in the dust. They come from a variety of villages in the area, with Quechan as the native language. It was explained that there's a bit of prejudice towards Quechan culture in Cusco and other large cities, with a lot of pressure on people speaking Spanish rather than Quechan (or Aramaya). I felt like a bit of a cock sometimes greeting them along the trail with a bouyant "Buenos Dias !", but then again it was the only common means of communication. Well, that and handing out the coca leaves, which were always well received. The undaunted adventurers, totally knackered at the top of the thousand metre climb to Warmiwañusca ("Dead Woman's Pass") - the highest point of the trek at 4,200 masl. The trial winds it's way up, down and around numerous different peaks, and the weather is extremely changeable with several microclimates operating at different elevations. On the way up to the pass the temperature dropped suddenly as a chill wind blew in from the top, and the air got noticeably thinner. Look at that, happy as children that have just heard their dad swear.

The undaunted adventurers, totally knackered at the top of the thousand metre climb to Warmiwañusca ("Dead Woman's Pass") - the highest point of the trek at 4,200 masl. The trial winds it's way up, down and around numerous different peaks, and the weather is extremely changeable with several microclimates operating at different elevations. On the way up to the pass the temperature dropped suddenly as a chill wind blew in from the top, and the air got noticeably thinner. Look at that, happy as children that have just heard their dad swear. The downward spiral from Dead Woman's Pass. There are three high altitude passes along the way and the inclines are hard going in places. Altitude sickness thankfully wasn't so much of a problem along the trail for us, and I took advantage of the local custom of chewing Coca leaves to alleviate the symptoms of tingling extremeties and general knackerdness. They initially tasted like dried tea, but soon took on the consistency of wet grass at the bottom of a mower box. Yes, these are the same leaves that are used as the base ingredient for cocaine (scandalous !), but rest assured that's about all you can say in terms of similarity. Chewing coca is a big part of Andean culture, and given the perceived link to the illegal narcotics that flood the cities in the developed world, it's no wonder it's largely misunderstood and demonised by other countries' govenments. I learned a bit about this in the excellent Coca Museum in La Paz - coca had been a part of indiginous Andean cultures for thousands of years before the Conquistadores arrived. It was proclaimed to be 'demonic' despite the relatively mild effects and the fact that it was essential for coping with the excruciating work in the mines. Effects of chewing coca include a reduced appetite, a perceived increase in energy and increased ability to breathe properly in the thin air of the highlands. Note that there is actually the same amount of oxygen in the air up here, it's the pressure that is reduced, meaning that it's far more difficult to get the necessary amount pushed into the lungs (which amounts to the same thing, really). In any case, coca was so necessary to daily life in the hard times of the Spanish conquest that it was eventually worth more than the equivalent weight in either gold or silver (not that there was any shortage of that either, at least not before it was nicked). Over in Bolivia, Evo Morales has promised to legalize the cultivation of coca, asserting it's difference to processed cocaine (which is sure to get up the nose of the U.S.)

The downward spiral from Dead Woman's Pass. There are three high altitude passes along the way and the inclines are hard going in places. Altitude sickness thankfully wasn't so much of a problem along the trail for us, and I took advantage of the local custom of chewing Coca leaves to alleviate the symptoms of tingling extremeties and general knackerdness. They initially tasted like dried tea, but soon took on the consistency of wet grass at the bottom of a mower box. Yes, these are the same leaves that are used as the base ingredient for cocaine (scandalous !), but rest assured that's about all you can say in terms of similarity. Chewing coca is a big part of Andean culture, and given the perceived link to the illegal narcotics that flood the cities in the developed world, it's no wonder it's largely misunderstood and demonised by other countries' govenments. I learned a bit about this in the excellent Coca Museum in La Paz - coca had been a part of indiginous Andean cultures for thousands of years before the Conquistadores arrived. It was proclaimed to be 'demonic' despite the relatively mild effects and the fact that it was essential for coping with the excruciating work in the mines. Effects of chewing coca include a reduced appetite, a perceived increase in energy and increased ability to breathe properly in the thin air of the highlands. Note that there is actually the same amount of oxygen in the air up here, it's the pressure that is reduced, meaning that it's far more difficult to get the necessary amount pushed into the lungs (which amounts to the same thing, really). In any case, coca was so necessary to daily life in the hard times of the Spanish conquest that it was eventually worth more than the equivalent weight in either gold or silver (not that there was any shortage of that either, at least not before it was nicked). Over in Bolivia, Evo Morales has promised to legalize the cultivation of coca, asserting it's difference to processed cocaine (which is sure to get up the nose of the U.S.) The attraction of the trail is not just the endless walking, sweating and lack of sleep. No, there's also an abundance of archaeological sites to explore. The stonework in these areas varied in appearance and construction techniques, but some it was utterly amazing, especially considering that iron and steel were not used in this area (gold and silver were). Some of it was shaped around stone formations found naturally, adding a great deal of strength, but the brickwork itself was exceptionally precise. Only hairline gaps were visible between blocks, and they were constructed in such a way to be virtually untouched by the earthquakes that rocked the area (unlike the later Spanish churches, which all collapsed). The terraces along the side of this peak are standard features at many of the sites in the area - opinions differ as to what purpose they serve, but it's mostly accepted that they serve as retaining walls - preventing erosion and landslides during the heavy rainfall in the wet season. Also present at the sites were wall holes for burials (mummification was extensively practiced, in the belief that when a person dies they should be returned to the earth and later resurrected). Percy also explained some of the more gruesome practices that took place including animal and human sacrifices - quite a few of the young women in the area were deliberately put to death. Those considered to be the most physically beautiful (provided they had not had their first menstruation) got the short end of the stick, as a sacrifice of this kind was considered to be an aid to the fertility of the land. Allegedly there was some sort of acclaim or prestige in this, as you would be acting as a sort of bridge between the human world and the spirit world, though I think humble anonymity would be much preferable.

The attraction of the trail is not just the endless walking, sweating and lack of sleep. No, there's also an abundance of archaeological sites to explore. The stonework in these areas varied in appearance and construction techniques, but some it was utterly amazing, especially considering that iron and steel were not used in this area (gold and silver were). Some of it was shaped around stone formations found naturally, adding a great deal of strength, but the brickwork itself was exceptionally precise. Only hairline gaps were visible between blocks, and they were constructed in such a way to be virtually untouched by the earthquakes that rocked the area (unlike the later Spanish churches, which all collapsed). The terraces along the side of this peak are standard features at many of the sites in the area - opinions differ as to what purpose they serve, but it's mostly accepted that they serve as retaining walls - preventing erosion and landslides during the heavy rainfall in the wet season. Also present at the sites were wall holes for burials (mummification was extensively practiced, in the belief that when a person dies they should be returned to the earth and later resurrected). Percy also explained some of the more gruesome practices that took place including animal and human sacrifices - quite a few of the young women in the area were deliberately put to death. Those considered to be the most physically beautiful (provided they had not had their first menstruation) got the short end of the stick, as a sacrifice of this kind was considered to be an aid to the fertility of the land. Allegedly there was some sort of acclaim or prestige in this, as you would be acting as a sort of bridge between the human world and the spirit world, though I think humble anonymity would be much preferable. So, did I suffer from vertigo along the trail ? Amazingly, for the most part I just got on with it, and concentrating on pumping the legs and getting up the slopes, trying to bite whole chunks of oxygen out of the thinning air. I had my concerns before the start as to how developed the trail was going to be - as in I had a horrible vision that big parts of it would be concrete steps, safety rails and all the trappings of a comfortable tourist experience. I'm happy to report that this was not the case at all, and there was pretty much no safety net the whole way. Perhaps a token piece of wooden railing on some rickety bridge somewhere, for about a metre at a time. The drops were sheer in a lot of places, but it wasn't until Machu Picchu itself that I had time to think about what I was doing, and some proper hesitancy set in (I saw one poor girl bawling her head off at the top of the Sundial). Let me explain what this sort of vertigo is like ... it's not that I just feel as if there's a danger of falling over the edge, it's as if I've already gone over. So you can imagine my horror when I heard that one of our group had done exactly that, whilst speeding along a wet cliff edge on the descent to Machu Picchu (this section inspires some seriously childish and outright dangerous behaviour as everyone tries to be first to the Sun Gate and beyond). I'm sure he realises the seriousness of the mistake now, but he had a very lucky escape in being able to grab some vines as soon as he went over. He was also extremely lucky that there were other people who noticed and were able to yank him back up - it could very, very easily have ended in tragedy.

So, did I suffer from vertigo along the trail ? Amazingly, for the most part I just got on with it, and concentrating on pumping the legs and getting up the slopes, trying to bite whole chunks of oxygen out of the thinning air. I had my concerns before the start as to how developed the trail was going to be - as in I had a horrible vision that big parts of it would be concrete steps, safety rails and all the trappings of a comfortable tourist experience. I'm happy to report that this was not the case at all, and there was pretty much no safety net the whole way. Perhaps a token piece of wooden railing on some rickety bridge somewhere, for about a metre at a time. The drops were sheer in a lot of places, but it wasn't until Machu Picchu itself that I had time to think about what I was doing, and some proper hesitancy set in (I saw one poor girl bawling her head off at the top of the Sundial). Let me explain what this sort of vertigo is like ... it's not that I just feel as if there's a danger of falling over the edge, it's as if I've already gone over. So you can imagine my horror when I heard that one of our group had done exactly that, whilst speeding along a wet cliff edge on the descent to Machu Picchu (this section inspires some seriously childish and outright dangerous behaviour as everyone tries to be first to the Sun Gate and beyond). I'm sure he realises the seriousness of the mistake now, but he had a very lucky escape in being able to grab some vines as soon as he went over. He was also extremely lucky that there were other people who noticed and were able to yank him back up - it could very, very easily have ended in tragedy. The scene that greeted us as the sun went down just before the third night's camping at Chakiqocha. The following day involved a dizzying and joint-worrying descent of around a thousand metres before rolling in to camp at Wiñawayna (meaning "Forever Young" - you will be if you fall over the bloody edge). For the preceeding days leading up to this we had walked longer than most other groups in order to secure campsites further along the trail, with the idea being that on the last night we could camp 10 minutes from the gated entrance to the last descent. This meant getting the relative luxury of a lie in until 4am, but also necessitated camping on the edge of cliffs so steep that getting up for a pee in the middle of the night was a life or death exercise. I'm not sure if it was the sudden increase in oxygen, or the fact that I was lying on a slope leading off into the void, but I felt highly agitated the whole night and had serious trouble sleeping (even by the standards of an arch insomniac like myself). We then had a frenetic run down the cliff tracks in the pitch dark, flashlights flailing, so that we could position ourselves for a lead along the trail proper. Fat lot of good it did me, as I sprained my ankle five minutes after getting onto it. Normally this would just mean getting ice on it immediately and resting up ... however I had to hike six more kilometres and could not get a good look the rapidly forming egg until the evening. Thus I was hobbling around for a good long while afterwards. My weak ankles are a legacy of injuries sustained from nearly ten years of drunken skateboarding, from the multi-stories of Windsor to the gravel plagued slopes of Southbank. Like a lot of other teenage pursuits, my only regret is that I didn't do it more before the consequences caught up with me.

The scene that greeted us as the sun went down just before the third night's camping at Chakiqocha. The following day involved a dizzying and joint-worrying descent of around a thousand metres before rolling in to camp at Wiñawayna (meaning "Forever Young" - you will be if you fall over the bloody edge). For the preceeding days leading up to this we had walked longer than most other groups in order to secure campsites further along the trail, with the idea being that on the last night we could camp 10 minutes from the gated entrance to the last descent. This meant getting the relative luxury of a lie in until 4am, but also necessitated camping on the edge of cliffs so steep that getting up for a pee in the middle of the night was a life or death exercise. I'm not sure if it was the sudden increase in oxygen, or the fact that I was lying on a slope leading off into the void, but I felt highly agitated the whole night and had serious trouble sleeping (even by the standards of an arch insomniac like myself). We then had a frenetic run down the cliff tracks in the pitch dark, flashlights flailing, so that we could position ourselves for a lead along the trail proper. Fat lot of good it did me, as I sprained my ankle five minutes after getting onto it. Normally this would just mean getting ice on it immediately and resting up ... however I had to hike six more kilometres and could not get a good look the rapidly forming egg until the evening. Thus I was hobbling around for a good long while afterwards. My weak ankles are a legacy of injuries sustained from nearly ten years of drunken skateboarding, from the multi-stories of Windsor to the gravel plagued slopes of Southbank. Like a lot of other teenage pursuits, my only regret is that I didn't do it more before the consequences caught up with me. And at 2,400 masl sits Machu Picchu ("Old Peak"), at last. After all the hassle of hobbling up to the Sun Gate on a stick, I was greeted by the stunning sight of ... a load of fog. Fortunately it didn't last, and I made it down the gut wrenching gradients to join the rest of the group. Probably the best known, and least known about, archaeological site in South America. Lost to the rest of the world until 1911 when it was re-discovered by Hiram Bingham, an American historian at Yale. The site was covered with thick vegetation, and the main clearing and restoration efforts lasted from 1912 to 1915. Bingham was later accused of removing around 5,000 artifacts from the site. Despite efforts by the Peruvian government to get them back, they are still in the possesion of Yale. Left is the sort of scene you'd probably get on tourism adverts ... the soundtrack would probably be a load of dreamy synth pads, reverbed piano arpeggios and perhaps a frenetic Charango. Personally I'd add a sample of a shrieking bird of prey pouncing on a guinea pig and cracking it's skull open with razor sharp beak to feast on the nut flavoured brains inside. Which explains why I can never work in advertising ever again.

And at 2,400 masl sits Machu Picchu ("Old Peak"), at last. After all the hassle of hobbling up to the Sun Gate on a stick, I was greeted by the stunning sight of ... a load of fog. Fortunately it didn't last, and I made it down the gut wrenching gradients to join the rest of the group. Probably the best known, and least known about, archaeological site in South America. Lost to the rest of the world until 1911 when it was re-discovered by Hiram Bingham, an American historian at Yale. The site was covered with thick vegetation, and the main clearing and restoration efforts lasted from 1912 to 1915. Bingham was later accused of removing around 5,000 artifacts from the site. Despite efforts by the Peruvian government to get them back, they are still in the possesion of Yale. Left is the sort of scene you'd probably get on tourism adverts ... the soundtrack would probably be a load of dreamy synth pads, reverbed piano arpeggios and perhaps a frenetic Charango. Personally I'd add a sample of a shrieking bird of prey pouncing on a guinea pig and cracking it's skull open with razor sharp beak to feast on the nut flavoured brains inside. Which explains why I can never work in advertising ever again.The original construction of the city was thought to have started in about 1440, and was inhabited up to the Spanish conquest of 1532. It's thought that it was primarily a retreat for Incan nobility (who were disposed once the spanish arrived on the scene - the Quechan workers were spared as they obviously were needed for such things as farming and other labour). As mentioned, the quality of stonework in the area is exceptional, and insulation was provided in the form of a mixture of clay, cactus juice and sand. Much of the stone is white granite, which due to a very slow crystalization process naturally forms cracks and fissures - exploitable with a few well placed holes and stakes. Once cracked into shape, they were polished off to a fine grade with white sand. The Inca were no slouches when it came to disciplines like geometry as well, as the sundial accurately points to all corners of the compass (it's not known how this was achieved). Percy seemed to think that the tilt at the top of it matched the tilt of the earth itself, calibrated with respect to other sundials hundreds of miles away. If this is indeed true, it's pretty mind blowing as it was achieved without any form of modern positioning systems and no way of practically verifying it.

This spitting git is a Llama, standard sight on the trail and elsewhere in the highlands of Peru. Like the Alpaca, it's a distant relative of the camel, a fact told to me by a racist man standing next to one in Tasmania. The Alpaca also happens to be a local favourite in restaurants everywhere, and tastes like beef but tougher and saltier. At the end of the hike I also got to sample some Guinea Pig, which tasted not unlike duck. I'm glad I ate one of the bastards, as there were a few of them milling around on the trails, blocking the way and generally making things far more difficult than they needed to be. I can also add them to the list of Gross Things Ingested, not limited to scorpion (tastes like roasted soy), wood grubs (tastes like Wotsits) and cat food (tastes like cat's breath).

This spitting git is a Llama, standard sight on the trail and elsewhere in the highlands of Peru. Like the Alpaca, it's a distant relative of the camel, a fact told to me by a racist man standing next to one in Tasmania. The Alpaca also happens to be a local favourite in restaurants everywhere, and tastes like beef but tougher and saltier. At the end of the hike I also got to sample some Guinea Pig, which tasted not unlike duck. I'm glad I ate one of the bastards, as there were a few of them milling around on the trails, blocking the way and generally making things far more difficult than they needed to be. I can also add them to the list of Gross Things Ingested, not limited to scorpion (tastes like roasted soy), wood grubs (tastes like Wotsits) and cat food (tastes like cat's breath). THE OCHO !! There's only so much tramping you can do each day, and there was a fair bit of free time in the evenings (more than I would have liked really, as I had left all forms of entertainment back in Cusco). But the bored will adapt ! Favourite distractions included Sapo (literally "Toad") which involved throwing brass chunks at a realistically fashioned amphibian. Also cliff edge rounds of hackysack (yes the inevitable happened), and sixth form favourite "Shithead". Though I grew up with the orthodox rules of Windsor Boys School, I have no idea where the girls picked up the crackheaded idea that wildcards have to be played in sequence. And since when do you play below a six for crying out loud ? Everyone knows it's the eight. What the hell are they teaching kids today anyway ? Completely underprepared for the larger world. I think I displayed remarkable patience under the circumstances, especially as this is what my taxes are paying for. However, one excellent modification was turning it into an excuse for getting pissed, a language that transcends all cultural and educational barriers. When laying the now-neutered eight, the players will simultaneously roar "The Ocho !" as loud as they can, knock bottles and swig deep. I am told this is something to do with the film Dodgeball. I don't really care about that, all I know is that it scandalized all the other squares in the campsite and that I thought it was hilarious. The hand that Drew is about to play has not one, but three eights ... the resulting bellows almost derailed the train.

THE OCHO !! There's only so much tramping you can do each day, and there was a fair bit of free time in the evenings (more than I would have liked really, as I had left all forms of entertainment back in Cusco). But the bored will adapt ! Favourite distractions included Sapo (literally "Toad") which involved throwing brass chunks at a realistically fashioned amphibian. Also cliff edge rounds of hackysack (yes the inevitable happened), and sixth form favourite "Shithead". Though I grew up with the orthodox rules of Windsor Boys School, I have no idea where the girls picked up the crackheaded idea that wildcards have to be played in sequence. And since when do you play below a six for crying out loud ? Everyone knows it's the eight. What the hell are they teaching kids today anyway ? Completely underprepared for the larger world. I think I displayed remarkable patience under the circumstances, especially as this is what my taxes are paying for. However, one excellent modification was turning it into an excuse for getting pissed, a language that transcends all cultural and educational barriers. When laying the now-neutered eight, the players will simultaneously roar "The Ocho !" as loud as they can, knock bottles and swig deep. I am told this is something to do with the film Dodgeball. I don't really care about that, all I know is that it scandalized all the other squares in the campsite and that I thought it was hilarious. The hand that Drew is about to play has not one, but three eights ... the resulting bellows almost derailed the train.

4 Comments:

...and the photos just get better. The one of the track and cloud is something else.

By Dan, at 6:41 PM

Dan, at 6:41 PM

Heh, of course I was an expert on Andean culture long before going to Peru, having seen those guys with the panpipes tootle away on Reading high street every Saturday morning.

Rich, I think DHL Peru might be a bit unreliable this time of year, might take a bit of time to get there :p

Feliz Navid everyone !

By James, at 12:40 PM

James, at 12:40 PM

Wonderful photos and blog James. We have been away for Christmas, so its nice to get back and catch up with you both.

Happy New Year

love Sally and Keith

By Anonymous, at 9:18 AM

Anonymous, at 9:18 AM

you are such an eloquent writer, James. Anyway, hope you're enjoying yourself, and look forward to the next entry!

By Kristin, at 8:17 PM

Kristin, at 8:17 PM

Post a Comment

<< Home