Bloody Computers

Back to the throng of Bangkok for a rest and a chance to decompress after being in Pa Do Tha and teaching the kids. We've spent so much time here now that it sort of feels like a second home when coming back to it now. We arrived to scenes of two significant events - the build up to the World Cup (mercifully downplayed here - I'm certainly glad I was out of the country for the inevitable blanket coverage at home), but more importantly in the eyes of your average Thai, the King's 60th anniversary of being on the throne. Anyone who has been to Thailand will have an idea of the reverance with which the King is held, the scenes locally were utter madness in any direction.

Back to the throng of Bangkok for a rest and a chance to decompress after being in Pa Do Tha and teaching the kids. We've spent so much time here now that it sort of feels like a second home when coming back to it now. We arrived to scenes of two significant events - the build up to the World Cup (mercifully downplayed here - I'm certainly glad I was out of the country for the inevitable blanket coverage at home), but more importantly in the eyes of your average Thai, the King's 60th anniversary of being on the throne. Anyone who has been to Thailand will have an idea of the reverance with which the King is held, the scenes locally were utter madness in any direction. The streets bulged with hundreds of people everywhere wearing yellow shirts bearing slogans such as "We Love The King" - I can't see this happening at home with our own royal family. The celebrations lasted for around four days, and the coverage on television even had the power to displace the World Cup, much to the chagrin of the assembled England fans, ho ho ho.

The streets bulged with hundreds of people everywhere wearing yellow shirts bearing slogans such as "We Love The King" - I can't see this happening at home with our own royal family. The celebrations lasted for around four days, and the coverage on television even had the power to displace the World Cup, much to the chagrin of the assembled England fans, ho ho ho. My sister Kate and her boyfriend Tim arrived on the tail end of this, and we spent an idyllic couple of weeks lounging around on beaches with them and stuffing ourselves stupid with grub. It was an absoloute joy to see them both as they arrived in Bangkok airport, and their faces were a total hoot when they saw that we'd come out to meet them !

My sister Kate and her boyfriend Tim arrived on the tail end of this, and we spent an idyllic couple of weeks lounging around on beaches with them and stuffing ourselves stupid with grub. It was an absoloute joy to see them both as they arrived in Bangkok airport, and their faces were a total hoot when they saw that we'd come out to meet them ! The first stop on the tourist trail was the floating market, where hundreds of rickety looking canoes barge their way around the waterways and tenacious merchants literally grab potential customers alongside with hooked rods.

The first stop on the tourist trail was the floating market, where hundreds of rickety looking canoes barge their way around the waterways and tenacious merchants literally grab potential customers alongside with hooked rods. The best thing I can say about it was that it was quite photogenic (rivalling Angkor Wat in terms of digital cameras per square metre), very very geared towards selling tat to tourists. I don't know what I was really expecting, I had this naive notion that there might be lots of locals buying their daily essentials, not the deluge of trinkets and crap that was actually on sale.

The best thing I can say about it was that it was quite photogenic (rivalling Angkor Wat in terms of digital cameras per square metre), very very geared towards selling tat to tourists. I don't know what I was really expecting, I had this naive notion that there might be lots of locals buying their daily essentials, not the deluge of trinkets and crap that was actually on sale.Continuing a vaguely nautical theme we decided to head off to some of Thailand's oft acclaimed islands. The first stop was Ko Phi Phi, near the top of the Andaman coast (on the left hand side of Thailand's 'tail) in the Krabi province, not that far from Phuket. Phi Phi is in fact a pair of islands, the developed Phi Phi Don and Phi Phi Lee - which has no permanant guesthouses but plenty of visitors by boat (and also the place where the film The Beach was filmed, obviously tourism rocketed in the area after this came out, leading to mass and unmanaged guesthouse developments).

Phi Phi was one of the worst hit areas in the Indian Ocean Tsunami of 2004 - the village of Ton Sai sits in the middle of the sand isthmus between the two main areas of the island. Buildings and lives were devastated as two huge waves from both sides of the isthmus met in the middle at around 10am on 26th December 2004. Evidence of the rebuilding effort is everywhere, and it's a tribute to the efforts of the people here that the place is almost completely back up and running.

Phi Phi was one of the worst hit areas in the Indian Ocean Tsunami of 2004 - the village of Ton Sai sits in the middle of the sand isthmus between the two main areas of the island. Buildings and lives were devastated as two huge waves from both sides of the isthmus met in the middle at around 10am on 26th December 2004. Evidence of the rebuilding effort is everywhere, and it's a tribute to the efforts of the people here that the place is almost completely back up and running. A longtail boat (so called because a spindly prop dips straight into the water from a large four stroke petrol engine) - a familiar site around the islands, acting as taxis and small fishing crafts.

A longtail boat (so called because a spindly prop dips straight into the water from a large four stroke petrol engine) - a familiar site around the islands, acting as taxis and small fishing crafts. They are pretty quick as there is nothing to them, but they're very affected by weight distribution - we four landlubbers were frequently told to stay in the middle as the boat was tipping precariously to one side. He needn't have worried - all Asker siblings have a well developed sense of balance due to the "Repel Boarders" technique of displacing others from sofas in the living room. Avast !

They are pretty quick as there is nothing to them, but they're very affected by weight distribution - we four landlubbers were frequently told to stay in the middle as the boat was tipping precariously to one side. He needn't have worried - all Asker siblings have a well developed sense of balance due to the "Repel Boarders" technique of displacing others from sofas in the living room. Avast !

Phi Phi Lee, at the beach where er, The Beach was filmed. I hope you enjoy the view, it cost us 200 baht a throw to step foot on the sand. Paying to go on a beach, eh ? Ppphhp.

I leapt at the chance to go snorkelling - my only previous experience being a few half arsed attempts in Kavos (where there really wasn't that much to see apart from discarded fag-ends). Kate and Tim were kind enough to pay for a day's snorkelling as a present for my birthday, with a handy DVD thrown in as a souvenir. On this you can observe not only the beauty of the near-depths but also Dan acting like some sort of barbarian nincompoop by trying to crack open a coconut husk on a rock - repeatedly and without success.

I leapt at the chance to go snorkelling - my only previous experience being a few half arsed attempts in Kavos (where there really wasn't that much to see apart from discarded fag-ends). Kate and Tim were kind enough to pay for a day's snorkelling as a present for my birthday, with a handy DVD thrown in as a souvenir. On this you can observe not only the beauty of the near-depths but also Dan acting like some sort of barbarian nincompoop by trying to crack open a coconut husk on a rock - repeatedly and without success.I had originally intended to go on an extended SCUBA diving trip whilst on the islands, as Thailand's many islands have some of the best dive sites in the world, and it's damn cheap to get PADI certification to boot. It has long been an ambition of mine to get into this properly - I had tried it before on an introductory lesson and loved the feeling of being able to move in three dimensions and investigate things at my leisure. My plans for this were scuppered a few years back when I had a bit of bother with one of my lungs, which meant an immediate end to my SCUBA designs. Alas I was to be told on Phi Phi that I would probably never be able to go diving with SCUBA equipment, as a previous problem of this sort would mean that nobody in their right mind would sign me off, much less take responsibility for it whilst under the water. A huge disappointment, but we had already gone snorkelling by this point, which was immensely enjoyable and satisfied some of my desire to see what was lying below the waves.

On our way to the second day's subaquatic antics - the sights this time were truly stunning, and by this time we'd got the hang of diving down towards the coral (taking care not to disturb it with hands or the fins). The visibility was particularly good, and the blues and crimsons of the fish were vivid - looking at the coral below was like something from another planet. One advantage of snorkelling of SCUBAing is that you are much more maneuverable, and more able to get alongside the fish as they swarm and idle around. A good trick is to get up close, then stop completely still - they seem to forget you're there - the sunlight glints and sparkles from hundreds of silver bodies centimetres from the face mask, and an eel flitted between my fingers.

On our way to the second day's subaquatic antics - the sights this time were truly stunning, and by this time we'd got the hang of diving down towards the coral (taking care not to disturb it with hands or the fins). The visibility was particularly good, and the blues and crimsons of the fish were vivid - looking at the coral below was like something from another planet. One advantage of snorkelling of SCUBAing is that you are much more maneuverable, and more able to get alongside the fish as they swarm and idle around. A good trick is to get up close, then stop completely still - they seem to forget you're there - the sunlight glints and sparkles from hundreds of silver bodies centimetres from the face mask, and an eel flitted between my fingers. Before Kate and Tim arrived, Dan and I had been dining intermittently at a superb vegetarian restaurant hidden away in the backstreets of Banglamphu, and we noted with interest that they offered classes to learn how to cook up to ten of their dishes. Kate and Tim also expressed an interest, so it was courtesy of Mai Kaidee (left, at the market) that we found ourselves learning how to cook up a variety of top quality nosh. Staying in Pa Do Tha had really brought home how easy it is to eat well with fresh ingredients and a minimum amount of fuss, against the backdrop of seeing how those ingredients are grown and harvested. I have also just finished reading Guns, Germs and Steel by Jared Diamond - a brief history of the last 13,000 years which argues that advanced civilisation, invention and resistance to disease became possible through the rise of sedentary farming - groups of people with a stable and rich source of food are able to support a more diverse type of society when the majority of people do not have to directly hunt or gather their own food supply (and as a side effect are able to develop arms and go and impose their will on weaker societies - oh well). All of this got me thinking about my own diet and eating habits - my cullinery cock-ups at home are famously bad, though the floor has often been well fed. When living away from home as I have done for the past couple of years, it's no secret that left to my own devices I tend towards convenience (and thus processed crap, pretty far removed from the wholesome stuff on the hills). It turns out that this does not have to be the case ! Eating well apparantly can be quite easy (and more importantly, quick). Mai certainly seems to think so - she has been cooking vegetarian food around Bangkok since 1988, and through sheer hard work now has three remarkably busy restaurants open in the area around Banglamphu. She has plans to open another internationally, perhaps in London, and her guest book is chock full of praise from people all over the world. She is notable also for popularizing the use of brown rice - unprocessed rice which apart from being extremely nutritious is also (in my opinion) nicer than bland old white rice. Traditionally it was seen as low grade rice, used to feed prisoners or dogs, but they may have been getting the better deal all those years.

Before Kate and Tim arrived, Dan and I had been dining intermittently at a superb vegetarian restaurant hidden away in the backstreets of Banglamphu, and we noted with interest that they offered classes to learn how to cook up to ten of their dishes. Kate and Tim also expressed an interest, so it was courtesy of Mai Kaidee (left, at the market) that we found ourselves learning how to cook up a variety of top quality nosh. Staying in Pa Do Tha had really brought home how easy it is to eat well with fresh ingredients and a minimum amount of fuss, against the backdrop of seeing how those ingredients are grown and harvested. I have also just finished reading Guns, Germs and Steel by Jared Diamond - a brief history of the last 13,000 years which argues that advanced civilisation, invention and resistance to disease became possible through the rise of sedentary farming - groups of people with a stable and rich source of food are able to support a more diverse type of society when the majority of people do not have to directly hunt or gather their own food supply (and as a side effect are able to develop arms and go and impose their will on weaker societies - oh well). All of this got me thinking about my own diet and eating habits - my cullinery cock-ups at home are famously bad, though the floor has often been well fed. When living away from home as I have done for the past couple of years, it's no secret that left to my own devices I tend towards convenience (and thus processed crap, pretty far removed from the wholesome stuff on the hills). It turns out that this does not have to be the case ! Eating well apparantly can be quite easy (and more importantly, quick). Mai certainly seems to think so - she has been cooking vegetarian food around Bangkok since 1988, and through sheer hard work now has three remarkably busy restaurants open in the area around Banglamphu. She has plans to open another internationally, perhaps in London, and her guest book is chock full of praise from people all over the world. She is notable also for popularizing the use of brown rice - unprocessed rice which apart from being extremely nutritious is also (in my opinion) nicer than bland old white rice. Traditionally it was seen as low grade rice, used to feed prisoners or dogs, but they may have been getting the better deal all those years. Spring Roll skins being made - just water, flour and salt.

Spring Roll skins being made - just water, flour and salt.Obviously being a purely vegetarian course this was of most practical use to Dan, but the recipes themselves looked easy enough to modify to cater for a carniverous diet too. I'm fairly indifferent as to whether a meal includes meat or not - much of the time when I'm cooking at home I can't be bothered using fish or chicken as it's too much hassle (and when you're talking about my cooking skills, leaving it out altogether is a lot safer). During the course of the morning, we alternated grub-spoiling responsibilities for the following :

- Tom Yan Soup

- Isaan

- Fried Veg with Ginger / Cashew Nuts

- Pad Thai, a favourite of street vendors on the Kao San road

- Peanut Sauce

- Spring Rolls - unfried and all the nicer for it

- Massaman Curry

- Green Thai Curry

- Pumpkin Hummus

- Green Papaya Salad

All of the food takes literally a few minutes to cook, in a single wok directly over a gas cannister. The important part is obviously the preparation - I had a go at cooking the peanut sauce and pumpkin hummus, they didn't turn out that badly even if I do say so myself. Which I do.

All of the food takes literally a few minutes to cook, in a single wok directly over a gas cannister. The important part is obviously the preparation - I had a go at cooking the peanut sauce and pumpkin hummus, they didn't turn out that badly even if I do say so myself. Which I do.

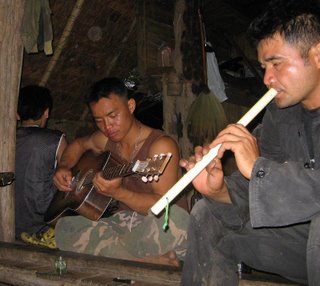

Mai frequently burst into song during the proceedings, warbling on with a ditty called the "Sap Cooking Song". I think the lyrics translate as something like "Yum yum yum yum yuuuuumm !". Not inappropriate at all - every one of the leguminous feasts were tasty, but we were given a bit of a treat with the dessert - brown rice and mango sticky pudding. It were grand.

Mai frequently burst into song during the proceedings, warbling on with a ditty called the "Sap Cooking Song". I think the lyrics translate as something like "Yum yum yum yum yuuuuumm !". Not inappropriate at all - every one of the leguminous feasts were tasty, but we were given a bit of a treat with the dessert - brown rice and mango sticky pudding. It were grand.